David Weber

On Basilisk Station

PROLOGUE

The ticking of the conference room's antique clock was deafening as the Hereditary President of the People's Republic of Haven stared at his military cabinet. The secretary of the economy looked away uncomfortably, but the secretary of war and her uniformed subordinates were almost defiant.

"Are you serious?" President Harris demanded.

"I'm afraid so," Secretary Frankel said unhappily. He shuffled through his memo chips and made himself meet the president's eyes. "The last three quarters all confirm the projection, Sid." He glowered sideways at his military colleague. "It's the naval budget. We can't keep adding ships this way without—"

"If we don't keep adding them," Elaine Dumarest broke in sharply, "the wheels come off. We're riding a neotiger, Mr. President. At least a third of the occupied planets still have crackpot `liberation' groups, and even if they didn't, everyone on our borders is arming to the teeth. It's only a matter of time until one of them jumps us."

"I think you're overreacting, Elaine," Ronald Bergren put in. The Secretary for Foreign Affairs rubbed his pencil-thin mustache and frowned at her. "Certainly they're arming—I would be, too, in their place—but none of them are strong enough to take us on."

"Perhaps not just now," Admiral Parnell said bleakly, "but if we get tied down elsewhere or any large-scale revolt breaks out, some of them are going to be tempted into trying a smash and grab. That's why we need more ships. And, with all due respect to Mr. Frankel," the CNO added, not sounding particularly respectful, "it isn't the Fleet budget that's breaking the bank. It's the increases in the Basic Living Stipend. We've got to tell the Dolists that any trough has a bottom and get them to stop swilling long enough to get our feet back under us. If we could just get those useless drones off our backs, even for a few years—"

"Oh, that's a wonderful idea!" Frankel snarled. "Those BLS increases are all that's keeping the mob in check! They supported the wars to support their standard of living, and if we don't—"

"That's enough!" President Harris slammed his hand down on the table and glared at them all in the shocked silence. He let the stillness linger a moment, then leaned back and sighed. "We're not going to achieve anything by calling names and pointing fingers," he said more mildly. "Let's face it—the DuQuesene Plan hasn't proved the answer we thought it would."

"I have to disagree, Mr. President," Dumarest said. "The basic plan remains sound, and it's not as if we have any other choice now. We simply failed to make sufficient allowance for the expenses involved."

"And for the revenues it would generate," Frankel added in a gloomy tone. "There's a limit to how hard we can squeeze the planetary economies, but without more income, we can't maintain our BLS expenditures and produce a military powerful enough to hold what we've got."

"How much time do we have?" Harris asked.

"I can't say for certain. I can paper over the cracks for a while, maybe even maintain a facade of affluence, by robbing Peter to pay Paul. But unless the spending curves change radically or we secure a major new source of revenue, we're living on borrowed time, and it's only going to get worse." He smiled without humor. "It's a pity most of the systems we've acquired weren't in much better economic shape than we were."

"And you're certain we can't reduce Fleet expenditures, Elaine?"

"Not without running very grave risks, Mr. President. Admiral Parnell is perfectly correct about how our neighbors will react if we waver." It was her turn to smile grimly. "I suppose we've taught them too well."

"Maybe we have," Parnell said, "but there's an answer to that." Eyes turned to him, and he shrugged. "Knock them off now. If we take out the remaining military powers on our frontiers, we can probably cut back to something more like a peace-keeping posture of our own."

"Jesus, Admiral!" Bergren snorted. "First you tell us we can't hold what we've got without spending ourselves into exhaustion, and now you want to kick off a whole new series of wars? Talk about the mysteries of the military mind—!"

"Hold on a minute, Ron," Harris murmured. He cocked his head at the admiral. "Could you pull it off, Amos?"

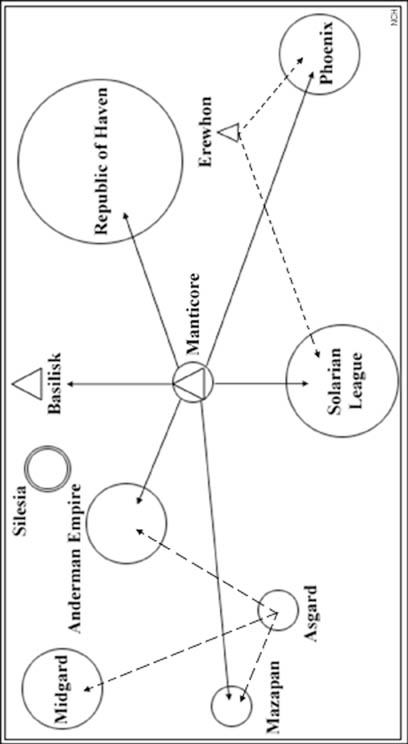

"I believe so," Parnell replied more cautiously. "The problem would be timing." He touched a button and a holo map glowed to life above the table. The swollen sphere of the People's Republic crowded its northeastern quadrant, and he gestured at a rash of amber and red star systems to the south and west. "There are no multi-system powers closer than the Anderman Empire," he pointed out. "Most of the single-system governments are strictly small change; we could blow out any one of them with a single task force, despite their armament programs. What makes them dangerous is the probability that they'll get organized as a unit if we give them time."

Harris nodded thoughtfully, but reached out and touched one of the beads of light that glowed a dangerous blood-red. "And Manticore?" he asked.

"That's the joker in the deck," Parnell agreed. "They're big enough to give us a fight, assuming they've got the guts for it."

"So why not avoid them, or at least leave them for last?" Bergren asked. "Their domestic parties are badly divided over what to do about us—couldn't we chop up the other small fry first?"

"We'd be in worse shape if we did," Frankel objected. He touched a button of his own, and two-thirds of the amber lights on Parnell's map turned a sickly gray-green. "Each of those systems is almost as far in the hole economically as we are," he pointed out. "They'll actually cost us money to take over, and the others are barely break-even propositions. The systems we really need are further south, down towards the Erewhon Junction, or over in the Silesian Confederacy to the west."

"Then why not grab them straight off?" Harris asked.

"Because Erewhon has League membership, Mr. President," Dumarest replied, "and going south might convince the League we're threatening its territory. That could be, ah, a bad idea." Heads nodded around the table. The Solarian League had the wealthiest, most powerful economy in the known galaxy, but its foreign and military policies were the product of so many compromises that they virtually did not exist, and no one in this room wanted to irritate the sleeping giant into evolving ones that did.

"So we can't go south," Dumarest went on, "but going west instead brings us right back to Manticore."

"Why?" Frankel asked. "We could take Silesia without ever coming within a hundred light-years of Manticore—just cut across above them and leave them alone."

"Oh?" Parnell challenged. "And what about the Manticore Wormhole Junction? Its Basilisk terminus would be right in our path. We'd almost have to take it just to protect our flank, and even if we didn't, the Royal Manticoran Navy would see the implications once we started expanding around their northern frontier. They'd have no choice but to try to stop us."

"We couldn't cut a deal with them?" Frankel asked Bergren, and the foreign secretary shrugged.

"The Manticoran Liberal Party can't find its ass with both hands where foreign policy is concerned, and the Progressives would probably dicker, but they aren't in control; the Centrists and Crown Loyalists are. They hate our guts, and Elizabeth III hates us even more than they do. Even if the Liberals and Progressives could turn the Government out, the Crown would never negotiate with us."

"Um." Frankel plucked at his lip, then sighed. "Too bad, because there's another point. We're in bad enough shape for foreign exchange, and three-quarters of our foreign trade moves through the Manticore Junction. If they close it against us, it'll add months to transit times ... and costs."

"Tell me about it," Parnell said sourly. "That damned junction also gives their navy an avenue right into the middle of the Republic through the Trevor's Star terminus."

"But if we knocked them out, then we'd hold the Junction," Dumarest murmured. "Think what that would do for our economy."

Frankel looked up, eyes glowing with sudden avarice, for the junction gave the Kingdom of Manticore a gross system product seventy-eight percent that of the Sol System itself. Harris noted his expression and gave a small, ugly smile.

"All right, let's look at it. We're in trouble and we know it. We have to keep expanding. Manticore is in the way, and taking it would give our economy a hefty shot in the arm. The problem is what we do about it."

"Manticore or not," Parnell said thoughtfully, "we have to pinch out these problem spots to the southwest." He gestured at the systems Frankel had dyed gray-green. "It'd be a worthwhile preliminary to position us against Manticore, anyway. But if we can do it, the smart move would be to take out Manticore first and then deal with the small fry."

"Agreed," Harris nodded. "Any ideas on how we might do that?"

"Let me get with my staff, Mr. President. I'm not sure yet, but the Junction could be a two-edged sword if we handle it right... ." The admiral's voice trailed off, then he shook himself. "Let me get with my staff," he repeated. "Especially with Naval Intelligence. I've got an idea, but I need to work on it." He cocked his head. "I can probably have a report, one way or the other, for you in about a month. Will that be acceptable?"

"Entirely, Admiral," Harris said, and adjourned the meeting.

CHAPTER ONE

The fluffy ball of fur in Honor Harrington's lap stirred and put forth a round, prick-eared head as the steady pulse of the shuttle's thrusters died. A delicate mouth of needle-sharp fangs yawned, and then the treecat turned its head to regard her with wide, grass-green eyes.

"Bleek?" it asked, and Honor chuckled softly.

"`Bleek' yourself," she said, rubbing the ridge of its muzzle. The green eyes blinked, and four of the treecat's six limbs reached out to grip her wrist in feather-gentle hand-paws. She chuckled again, pulling back to initiate a playful tussle, and the treecat uncoiled to its full sixty-five centimeters (discounting its tail) and buried its true-feet in her midriff with the deep, buzzing hum of its purr. The hand-paws tightened their grip, but the murderous claws—a full centimeter of curved, knife-sharp ivory—were sheathed. Honor had once seen similar claws used to rip apart the face of a human foolish enough to threaten a treecat's companion, but she felt no concern. Except in self-defense (or Honor's defense) Nimitz would no more hurt a human being than turn vegetarian, and treecats never made mistakes in that respect.

She extricated herself from Nimitz's grasp and lifted the long, sinuous creature to her shoulder, a move he greeted with even more enthusiastic purrs. Nimitz was an old hand at space travel and understood shoulders were out of bounds aboard small craft under power, but he also knew treecats belonged on their companions' shoulders. That was where they'd ridden since the first 'cat adopted its first human five Terran centuries before, and Nimitz was a traditionalist.

A flat, furry jaw pressed against the top of her head as Nimitz sank his four lower sets of claws into the specially padded shoulder of her uniform tunic. Despite his long, narrow body, he was a hefty weight—almost nine kilos—even under the shuttle's single gravity, but Honor was used to it, and Nimitz had learned to move his center of balance in from the point of her shoulder. Now he clung effortlessly to his perch while she collected her briefcase from the empty seat beside her. Honor was the half-filled shuttle's senior passenger, which had given her the seat just inside the hatch. It was a practical as well as a courteous tradition, since the senior officer was always last to board and first to exit.

The shuttle quivered gently as its tractors reached out to the seventy-kilometer bulk of Her Majesty's Space Station Hephaestus, the Royal Manticoran Navy's premiere shipyard, and Nimitz sighed his relief into Honor's short-cropped mass of feathery, dark brown hair. She smothered another grin and rose from her bucket seat to twitch her tunic straight. The shoulder seam had dipped under Nimitz's weight, and it took her a moment to get the red-and-gold navy shoulder flash with its roaring, lion-headed, bat-winged manticore, spiked tail poised to strike, back where it belonged. Then she plucked the beret from under her left epaulet. It was the special beret, the white one she'd bought when they gave her Hawkwing, and she chivied Nimitz's jaw gently aside and settled it on her head. The treecat put up with her until she had it adjusted just so, then shoved his chin back into its soft warmth, and she felt her face crease in a huge grin as she turned to the hatch.

That grin was a violation of her normally severe "professional expression," but she was entitled. Indeed, she felt more than mildly virtuous for holding herself to a grin when what she really wanted to do was spin on her toes, fling her arms wide, and carol her delight to her no-doubt shocked fellow passengers. But she was almost twenty-four years old—over forty Terran standard years—and it would never, never have done for a commander of the Royal Manticoran Navy to be so undignified, even if she was about to assume command of her first cruiser.

She smothered another chuckle, luxuriating in the unusual sense of complete and simple joy, and pressed a hand to the front of her tunic. The folded sheaf of archaic paper crackled at her touch—a curiously sensual, exciting sound—and she closed her eyes to savor it even as she savored the moment she'd worked so hard to reach.

Fifteen years—twenty-five T-years—since that first exciting, terrifying day on the Saganami campus. Two and a half years of Academy classes and running till she dropped. Four years working her way without patronage or court interest from ensign to lieutenant. Eleven months as sailing master aboard the frigate Osprey, and then her first command, a dinky little intrasystem LAC. It had massed barely ten thousand tons, with only a hull number and not even the dignity of a name, but God how she'd loved that tiny ship! Then more time as executive officer, a turn as tactical officer on a massive superdreadnought. And then—finally!—the coveted commanding officer's course after eleven grueling years. She'd thought she'd died and gone to heaven when they gave her Hawkwing, for the middle-aged destroyer had been her very first hyper-capable command, and the thirty-three months she'd spent in command had been pure, unalloyed joy, capped by the coveted Fleet "E" award for tactics in last year's war games. But this—!

The deck shuddered beneath her feet, and the light above the hatch blinked amber as the shuttle settled into Hephaestus's docking buffers, then burned a steady green as pressure equalized in the boarding tube. The panel slid aside, and Honor stepped briskly through it.

The shipyard tech manning the hatch at the far end of the tube saw the white beret of a starship's captain and the three gold stripes of a full commander on a space-black sleeve and came to attention, but his snappy response was flawed by a tiny hesitation as he caught sight of Nimitz. He flushed and twitched his eyes away, but Honor was used to that reaction. The treecats native to her home world of Sphinx were picky about which humans they adopted. Relatively few were seen off-world, but they refused to be parted from their humans even if those humans chose space-going careers, and the Lords of Admiralty had caved in on that point almost a hundred and fifty Manticoran years before. 'Cats rated a point-eight-three on the sentience scale, slightly above Beowulf's gremlins or Old Earth's dolphins, and they were empaths. Even now, no one had the least idea how their empathic links worked, but separating one from its chosen companion caused it intense pain, and it had been established early on that those favored by a 'cat were measurably more stable than those without. Besides, Crown Princess Adrienne had been adopted by a 'cat on a state visit to Sphinx. When Queen Adrienne of Manticore expressed her displeasure twelve years later at efforts to separate officers in her navy from their companions, the Admiralty found itself with no option but to grant a special exemption from its draconian "no pets" policy.

Honor was glad of it, though she'd been afraid it would be impossible to find time to spend with Nimitz when she entered the Academy. She'd known going in that those forty-five endless months on Saganami Island were deliberately planned to leave even midshipmen without 'cats too few hours to do everything they had to do. But while Academy instructors might suck their teeth and grumble when a plebe turned up with one of the rare 'cats, they recognized natural forces for which allowances must be made when they saw one. Besides, even the most "domesticated" 'cat retained the independence (and indestructibility) of his cousins in the wild, and Nimitz had seemed perfectly aware of the pressure she faced. All he needed was a little grooming, an occasional wrestling bout, a perch on her shoulder or lap while she pored over the book chips and to sleep curled neatly up on her pillow, and he was happy. Not that he'd been above looking mournful and pitiful to extort tidbits and petting from any unfortunate who crossed his path. Even Chief MacDougal, the terror of the first-form middies, had succumbed, carrying a suitable stash of the celery stalks the otherwise carnivorous treecats craved and sneaking them to Nimitz when he thought no one was looking. And, Honor reflected wryly, running Ms. Midshipman Harrington ragged to compensate for his weakness.

Her thoughts had carried her through the arrival gate to the concourse, and she looked about until she found the color-coded guide strip to the personnel tubes. She followed it, unburdened by any baggage, for she had none. All her meager personal possessions had been freighted up this morning, whisked away by stewards at the Advanced Tactical Course facility almost before she'd had time to pack.

She frowned a bit at that thought while she punched up a tube capsule. All the scramble to get her here seemed out of character for a navy that preferred to do things in an orderly fashion. When she'd been given Hawkwing, she'd known two months in advance; this time, she'd been literally snatched out of the ATC graduation ceremonies and hustled off to Admiral Courvosier's office with no warning at all.

The capsule arrived, and she stepped into it, still frowning and rubbing gently at the tip of her nose. Nimitz roused to lift his chin from the top of her beret and nipped her ear with the scolding tug he saved for the unfortunately frequent moments when his companion worried. Honor clicked her teeth gently at him and reached up to scratch his chest, but she didn't stop worrying, and he sighed in exasperation.

Now why, she wondered, was she so certain Courvosier had deliberately bustled her out of his office and off to her new assignment? The admiral was a bland-faced, cherubic little gnome of a man with a bent for creating demonic tac problems, and she'd known him for years. He'd been her Fourth Form Tactics instructor at the Academy, the one who'd recognized an inborn instinct and honed it into something she could command at will, not something that came and went. He'd spent hours working with her in private when other instructors worried about her basic math scores and, in a very real sense, had saved her career before it had actually begun, yet this time there'd been something almost evasive about him. She knew his congratulations and satisfied pride in her had been real, but she couldn't shake the impression that there'd been something else, as well. Ostensibly, the rush was all because of the need to get her to Hephaestus to shepherd her new ship through its refit in time for the upcoming Fleet exercise, yet HMS Fearless was only a single light cruiser, when all was said. It seemed unlikely her absence would critically shift the balance in maneuvers planned to exercise the entire Home Fleet!

No, something was definitely up, and she wished fervently that she'd had time for a full download before catching the shuttle. But at least all the rush had kept her from worrying herself into a swivet the way she had before taking Hawkwing over, and Lieutenant Commander McKeon, her new exec, had served on Fearless for almost two years, first as tactical officer and then as exec. He should be able to bring her up to speed on the refit Courvosier had been so oddly reluctant to discuss.

She shrugged and punched her destination into the capsule's routing panel, then set down her briefcase and resigned herself as it flashed away down the counter-grav tubeway. Despite a peak speed of well over seven hundred kilometers per hour, the capsule trip would take over fifteen minutes—assuming she was lucky enough not to hit too many stops en route.

The deck shivered gently underfoot. Few would have detected the tiny bobble as one quadrant of Hephaestus's gravity generators handed the tube off to another, but Honor noticed it. Not consciously, perhaps, but that minute quiver was part of a world which had become more real to her than the deep blue skies and chill winds of her childhood. It was like her own heartbeat, one of the tiny, uncountable stimuli that told her—instantly and completely—what was happening around her.

She watched the tube map display, shaking off thoughts of evasive admirals and other puzzles as her eyes tracked the blinking cursor of her capsule across it. Her hand rose to press the crispness of her orders once more, and she paused, almost surprised as she looked away from the map and glimpsed her reflection in the capsule's polished wall.

The face that gazed back should have looked different, reflecting the monumental change in her status, and it didn't. It was still all sharply defined planes and angles dominated by a straight, patrician nose (which, in her opinion, was the only remotely patrician thing about her) and devoid of the least trace of cosmetics. Honor had been told (once) that her face had "a severe elegance." She didn't know about that, but the idea was certainly better than the dread, "My, isn't she, um, healthy looking!" Not that "healthy" wasn't accurate, however depressing it might sound. She looked trim and fit in the RMN's black and gold, courtesy of her 1.35-gravity homeworld and a rigorous exercise regimen, and that, she thought, critically, was about the best she had to say about herself.

Most of the Navy's female officers had chosen to adopt the current planet-side fashion of long hair, often elaborately dressed and arranged, but Honor had decided long ago there was no point trying to make herself something she was not. Her hair-style was practical, with no pretensions to glamour. It was clipped short to accommodate vac helmets and bouts of zero-gee, and if its two-centimeter strands had a stubborn tendency to curl, it was neither blond, nor red, nor even black, just a highly practical, completely unspectacular dark brown. Her eyes were even darker, and she'd always thought their hint of an almond shape, inherited from her mother, made them look out of place in her strong-boned face, almost as if they'd been added as an afterthought. Their darkness made her pale complexion seem still paler, and her chin was too strong below her firm-lipped mouth. No, she decided once more, with a familiar shade of regret, it was a serviceable enough face, but there was no use pretending anyone would ever accuse it of radiant beauty ... darn it.

She grinned again, feeling the bubble of delight pushing her worries aside, and her reflection grinned back. It made her look like an urchin gloating over a hidden bag of candy, and she took herself firmly to task for the remainder of the trip, concentrating on a new CO's responsibility to look cool and collected, but it was hard. She'd done well to make commander so soon even with the Fleet's steady growth in the face of the Havenite threat, for the life-extending prolong process made for long careers. The Navy was well-supplied with senior officers, despite its expansion, and she came of yeoman stock, without the high-placed relatives or friends to nudge a naval career along. She'd known and accepted from the start that those with less competence but more exalted bloodlines would race past her. Well, they had, but she'd made it at last. A cruiser command, the dream of every officer worth her salt! So what if Fearless was twice her own age and little larger than a modern destroyer? She was still a cruiser, and cruisers were the Manticoran Navy's eyes and ears, its escorts and its raiders, the stuff of independent commands and opportunity.

And responsibility. That thought let her banish the grin at last, because if independent command was what every good officer craved, a captain all alone in the big dark had no one to appeal to. No one to take the credit or share the blame, for she was all alone, the final arbiter of her ship's fate and the direct, personal representative of her queen and kingdom, and if she failed that trust no power in the galaxy could save her.

The personnel capsule ghosted to a stop, and she stepped out into the spacious gallery of the spacedock, brown eyes hungry as they swept over her new command at last. HMS Fearless floated in her mooring beyond the tough, thick wall of armorplast, lean and sleek even under the clutter of work platforms and access tubes, and the pendant number "CL-56" stood out against the white hull just behind her forward impeller nodes. Yard mechs swarmed over her in the dock's vacuum, supervised by vacsuited humans, but most of the work seemed to be concentrated on the broadside weapon bays.

Honor stood motionless, watching through the armorplast, feeling Nimitz rise straight and tall on her shoulder to join her perusal, and an eyebrow quirked. Admiral Courvosier had mentioned that Fearless was undergoing a major refit, but what was going on out there seemed a bit more major than she'd anticipated. Which, coupled with his deliberate lack of detail, suggested something very special was in the wind, though Honor still couldn't imagine what could be important enough to turn the admiral all mysterious on her. Nor did it matter very much to her as she drank up her new command—her new command!—with avid eyes.

She never knew exactly how long she stood there before she managed to tear her attention away at last and head for the crew tube. The two Marine sentries stood at parade rest, watching her approach, then snapped to attention as she reached them.

She handed over her ID and watched approvingly as the senior man, a corporal, scrutinized it. They knew who she was, of course, unless the grapevine had died a sudden and unexpected death. Even if they hadn't, only one member of any ship's company was permitted the coveted white beret. But neither displayed the least awareness that their new mistress after God had arrived. The corporal handed back her ID folio with a salute, and she returned it and walked past them into the access tube.

She didn't look back, but the bulkhead mirror at the tube's first bend, intended to warn of oncoming traffic coming round the corner, let her watch the sentries as the corporal keyed his wrist com to alert the command deck that the new captain was on her way.

The scarlet band of a zero-gee warning slashed the access tube deck before her, and she felt Nimitz's claws sink deeper into her shoulder pad as she stepped over it. She launched herself into the graceful swim of free-fall as she passed out of Hephaestus's artificial gravity, and her pulse raced with quite unbecoming speed as she eeled down the passage. Another two minutes, she told herself. Only another two minutes.

Lieutenant Commander Alistair McKeon twitched his tunic straight and smothered a flare of annoyance as he stood by the entry port. He'd been buried in the bowels of a vivisected fire control station when the message came in. There'd been no time to shower or change into a fresh uniform, and he felt the sweat staining his blouse under his hastily donned tunic, but at least Corporal Levine's message had given him enough warning to collect the side party. Formal courtesies weren't strictly required from a ship in yard hands, but McKeon would take no chance of irritating a new captain. Besides, Fearless had a reputation to maintain, and—

His spine straightened, and a spasm of something very like pain went through him as his new captain rounded the tube's final bend. Her white beret gleamed under the lights, and he felt his face stiffen as he saw the sleek, cream-and-gray shape riding her shoulder. He hadn't known she had a treecat, and he smothered a fresh spurt of irrational resentment at the sight.

Commander Harrington floated easily down the last few meters of tube, then spun in midair and caught the final, scarlet-hued grab bar that marked the edge of Fearless's internal grav field. She crossed the interface like a gymnast dismounting from the rings to land lightly before him, and McKeon's sense of personal injury grew perversely stronger as he realized how little justice the photo in her personnel jacket had done her. Her triangular face had looked stern and forbidding, almost cold, in the file imagery, especially framed in the dark fuzz of her close-cropped hair, but the pictures had lied. They hadn't captured the life and vitality, the sharp-edged attractiveness. No one would ever call Commander Harrington "pretty," he thought, but she had something far more important. Those clean-cut, strong features and huge, dark brown eyes—exotically angular and sparkling with barely restrained delight despite her formal expression—discounted such ephemeral concepts as "pretty." She was herself, unique, impossible to confuse with anyone else, and that only made it worse.

McKeon met her scrutiny with a stolid expression and fought to suppress his confused, bitter resentment. He saluted sharply, the side party came to attention, and the bosun's calls shrilled. All activity stilled around the entry port, and her hand came up in an answering salute.

"Permission to come aboard?" Her voice was a cool, clear soprano, surprisingly light in a woman her size, for she easily matched McKeon's own hundred and eighty centimeters.

"Permission granted," he replied. It was a formality, but a very real one. Until she officially assumed command, Harrington was no more than a visitor aboard McKeon's ship.

"Thank you," she said, and stepped aboard as he stood back to clear the hatch.

He watched her chocolate-dark eyes sweep over the entry port and side party and wondered what she was thinking. Her sculpted face made an excellent mask for her emotions (except for those glowing eyes, he thought sourly), and he hoped his own did the same. It wasn't really fair of him to resent her. A light cruiser simply wasn't a lieutenant commander's billet, but Harrington was almost five years—over eight T-years—younger than he. Not only was she a full commander, not only did the breast of her tunic bear the embroidered gold star denoting a previous hyper-capable command, but she looked young enough to be his daughter. Well, no, not that young, perhaps, but she could have been his niece. Of course, she was second-generation prolong. He'd checked the open portion of her record closely enough to know that, and the anti-aging treatments seemed to be proving even more effective for second— and third-generation recipients. Other parts of her record—like her penchant for unorthodox tactical maneuvers, and the CGM and Monarch's Thanks she'd earned saving lives when HMS Manticore's forward power room exploded—soothed his resentment a bit, but neither they nor knowing why she seemed so youthful could lessen the emotional impact of finding the slot he'd longed for so hopelessly filled by an officer who not only oozed the effortless magnetism he'd always envied in others but also looked as if she'd graduated from the Academy last year. Nor did the bright, unwavering regard the treecat bent upon him make him feel any better.

Harrington completed her inspection of the side party without comment, then turned back to him, and he smothered his resentment and turned to the next, formalized step of his responsibilities.

"May I escort you to the bridge, Ma'am?" he asked, and she nodded.

"Thank you, Commander," she murmured, and he led the way up-ship.

Honor stepped out of the bridge lift and looked around what was about to become her personal domain. The signs of a frenzied refit were evident, and puzzlement stirred afresh as she noted the chaos of tools and parts strewn across her tactical section. Nothing else even seemed disturbed. Darn it, what hadn't Admiral Courvosier told her about her ship?

But that was for the future. For now, she had other things to attend to, and she crossed to the captain's chair, surrounded by its nest of displays and readouts at the center of the bridge. Most of the displays were retracted into their storage positions, and she rested her hand for a moment on the panel concealing the tactical repeater display. She didn't sit down. By long tradition, that chair was barred to any captain before she'd read herself aboard, but she took her place beside it and coaxed Nimitz off her shoulder and onto its far arm, out of the intercom pickup's field. Then she set aside her briefcase, pressed a stud on the near arm, and listened to the clear, musical chime resounding through the ship.

All activity aboard Fearless stopped. Even the handful of visiting civilian techs slid out from under the consoles they were rewiring or crawled up out of the bowels of power rooms and shunting circuits as the all-hands signal sounded. Bulkhead intercom screens flicked to life with Honor's face, and she felt hundreds of eyes as they noted the distinctive white beret and sharpened to catch their first sight of the captain into whose keeping the Lords of Admiralty in their infinite wisdom had committed their lives.

She reached into her tunic, and paper crackled, whispering from every speaker, as she broke the seals and unfolded her orders.

"From Admiral Sir Lucien Cortez, Fifth Space Lord, Royal Manticoran Navy," she read in her crisp, cool voice, "to Commander Honor Harrington, Royal Manticoran Navy, Thirty-Fifth Day, Fourth Month, Year Two Hundred and Eighty After Landing. Madam: You are hereby directed and required to proceed aboard Her Majesty's Starship Fearless, CL-Five-Six, there to take upon yourself the duties and responsibilities of commanding officer in the service of the Crown. Fail not in this charge at your peril. By order of Admiral Sir Edward Janacek, First Lord of Admiralty, Royal Manticoran Navy, for Her Majesty the Queen."

She fell silent and refolded her orders without even glancing at the pickup. For almost five T-centuries, those formal phrases had marked the transfer of command aboard the ships of the Manticoran Navy. They were brief and stilted, but by the simple act of reading them aloud she had placed her crew under her authority, bound them to obey her upon pain of death. The vast majority of them knew nothing at all about her, and she knew equally little about them, and none of that mattered. They had just become her crew, their very lives dependent upon how well she did her job, and an icicle of awareness sang through her as she finished folding the heavy sheet of paper and turned once more to McKeon.

"Mr. Exec," she said formally, "I assume command."

"Captain," he replied with equal formality, "you have command."

"Thank you." She glanced at the duty quartermaster, reading his nameplate from across the bridge. "Make a note in the log, please, Chief Braun," she said, and turned back to the pickup and her watching crew. "I won't take up your time with any formal speeches, people. We have too much to do and too little time to do it in as it stands. Carry on."

She touched the stud again. The intercom screens went blank, and she lowered herself into the comfortable, contoured chair—her chair now. Nimitz swarmed back onto her shoulder with a slightly aggrieved flip of his tail, and she gestured for McKeon to join her.

The tall, heavyset exec crossed the bridge to her while the bustle of work resumed about them. His gray eyes met hers with, she thought, perhaps just an edge of discomfort ... or challenge. The thought surprised her, but he held out his hand in the traditional welcome to a new captain, and his deep voice was level.

"Welcome aboard, Ma'am," he said. "I'm afraid things are a bit of a mess just now, but we're pretty close to on schedule, and the dock master's promised me two more work crews starting next watch."

"Good." Honor returned his handshake, then stood and walked toward the gutted fire control section with him. "I have to admit to a certain amount of puzzlement, though, Mr. McKeon. Admiral Courvosier warned me we were due for a major refit, but he didn't mention any of this." She nodded at the open panels and unraveled circuit runs.

"I'm afraid we didn't have much choice, Ma'am. We could have handled the energy torpedoes with software changes, but the grav lance is basically an engineering system. Tying it into fire control requires direct hardware links to the main tactical system."

"Grav lance?" Honor didn't raise her voice, but McKeon heard the surprise under its cool surface, and it was his turn to raise an eyebrow.

"Yes, Ma'am." He paused. "Didn't anyone mention that to you?"

"No, they didn't." Honor's lips thinned in what might charitably have been called a smile, and she folded her hands deliberately behind her. "How much broadside armament did it cost us?" she asked after a moment.

"All four graser mounts," McKeon replied, and watched her shoulders tighten slightly.

"I see. And you mentioned energy torpedoes, I believe?"

"Yes, Ma'am. The yard's replaced—is replacing, rather—all but two broadside missile tubes with them."

"All but two?" The question was sharper this time, and McKeon hid an edge of bitter amusement. No wonder she sounded upset, if they hadn't even warned her! He'd certainly been upset when he found out what was planned.

"Yes, Ma'am."

"I see," she repeated, and inhaled. "Very well, Exec, what does that leave us?"

"We still have the thirty-centimeter laser mounts, two in each broadside, plus the missile launchers. After refit, we'll have the grav lance and fourteen torpedo generators, as well, and the chase armament is unchanged: two missile tubes and the sixty-centimeter spinal laser."

He watched her closely, and she didn't—quite—wince. Which, he reflected, spoke well for her self-control. Energy torpedoes were quick-firing, destructive, very difficult for point defense to stop... and completely ineffectual against a target protected by a military-grade sidewall. That, obviously, was the reason for the grav lance, yet if a grav lance could (usually) burn out its target's sidewall generators, it was slow-firing and had a very short maximum effective range. But if Captain Harrington was aware of that, she allowed no trace of it to color her voice.

"I see," she said yet again, and gave her head a little toss. "Very well, Mr. McKeon. I'm sure I've taken you away from something more useful than talking to me. Have my things been stowed?"

"Yes, Ma'am. Your steward saw to it."

"In that case, I'll be in my quarters examining the ship's books if you need me. I'd like to invite the officers to dine with me this evening—I see no point in letting introductions interfere with their duties now." She paused, as if reaching for another thought, then looked back at him. "Before then, I'll want to tour the ship and observe the work in progress. Will it be convenient for you to accompany me at fourteen-hundred?"

"Of course, Captain."

"Thank you. I'll see you then." She nodded and left the bridge without a backward glance.

"Bleek?" it asked, and Honor chuckled softly.

"`Bleek' yourself," she said, rubbing the ridge of its muzzle. The green eyes blinked, and four of the treecat's six limbs reached out to grip her wrist in feather-gentle hand-paws. She chuckled again, pulling back to initiate a playful tussle, and the treecat uncoiled to its full sixty-five centimeters (discounting its tail) and buried its true-feet in her midriff with the deep, buzzing hum of its purr. The hand-paws tightened their grip, but the murderous claws—a full centimeter of curved, knife-sharp ivory—were sheathed. Honor had once seen similar claws used to rip apart the face of a human foolish enough to threaten a treecat's companion, but she felt no concern. Except in self-defense (or Honor's defense) Nimitz would no more hurt a human being than turn vegetarian, and treecats never made mistakes in that respect.

She extricated herself from Nimitz's grasp and lifted the long, sinuous creature to her shoulder, a move he greeted with even more enthusiastic purrs. Nimitz was an old hand at space travel and understood shoulders were out of bounds aboard small craft under power, but he also knew treecats belonged on their companions' shoulders. That was where they'd ridden since the first 'cat adopted its first human five Terran centuries before, and Nimitz was a traditionalist.

A flat, furry jaw pressed against the top of her head as Nimitz sank his four lower sets of claws into the specially padded shoulder of her uniform tunic. Despite his long, narrow body, he was a hefty weight—almost nine kilos—even under the shuttle's single gravity, but Honor was used to it, and Nimitz had learned to move his center of balance in from the point of her shoulder. Now he clung effortlessly to his perch while she collected her briefcase from the empty seat beside her. Honor was the half-filled shuttle's senior passenger, which had given her the seat just inside the hatch. It was a practical as well as a courteous tradition, since the senior officer was always last to board and first to exit.

The shuttle quivered gently as its tractors reached out to the seventy-kilometer bulk of Her Majesty's Space Station Hephaestus, the Royal Manticoran Navy's premiere shipyard, and Nimitz sighed his relief into Honor's short-cropped mass of feathery, dark brown hair. She smothered another grin and rose from her bucket seat to twitch her tunic straight. The shoulder seam had dipped under Nimitz's weight, and it took her a moment to get the red-and-gold navy shoulder flash with its roaring, lion-headed, bat-winged manticore, spiked tail poised to strike, back where it belonged. Then she plucked the beret from under her left epaulet. It was the special beret, the white one she'd bought when they gave her Hawkwing, and she chivied Nimitz's jaw gently aside and settled it on her head. The treecat put up with her until she had it adjusted just so, then shoved his chin back into its soft warmth, and she felt her face crease in a huge grin as she turned to the hatch.

That grin was a violation of her normally severe "professional expression," but she was entitled. Indeed, she felt more than mildly virtuous for holding herself to a grin when what she really wanted to do was spin on her toes, fling her arms wide, and carol her delight to her no-doubt shocked fellow passengers. But she was almost twenty-four years old—over forty Terran standard years—and it would never, never have done for a commander of the Royal Manticoran Navy to be so undignified, even if she was about to assume command of her first cruiser.

She smothered another chuckle, luxuriating in the unusual sense of complete and simple joy, and pressed a hand to the front of her tunic. The folded sheaf of archaic paper crackled at her touch—a curiously sensual, exciting sound—and she closed her eyes to savor it even as she savored the moment she'd worked so hard to reach.

Fifteen years—twenty-five T-years—since that first exciting, terrifying day on the Saganami campus. Two and a half years of Academy classes and running till she dropped. Four years working her way without patronage or court interest from ensign to lieutenant. Eleven months as sailing master aboard the frigate Osprey, and then her first command, a dinky little intrasystem LAC. It had massed barely ten thousand tons, with only a hull number and not even the dignity of a name, but God how she'd loved that tiny ship! Then more time as executive officer, a turn as tactical officer on a massive superdreadnought. And then—finally!—the coveted commanding officer's course after eleven grueling years. She'd thought she'd died and gone to heaven when they gave her Hawkwing, for the middle-aged destroyer had been her very first hyper-capable command, and the thirty-three months she'd spent in command had been pure, unalloyed joy, capped by the coveted Fleet "E" award for tactics in last year's war games. But this—!

The deck shuddered beneath her feet, and the light above the hatch blinked amber as the shuttle settled into Hephaestus's docking buffers, then burned a steady green as pressure equalized in the boarding tube. The panel slid aside, and Honor stepped briskly through it.

The shipyard tech manning the hatch at the far end of the tube saw the white beret of a starship's captain and the three gold stripes of a full commander on a space-black sleeve and came to attention, but his snappy response was flawed by a tiny hesitation as he caught sight of Nimitz. He flushed and twitched his eyes away, but Honor was used to that reaction. The treecats native to her home world of Sphinx were picky about which humans they adopted. Relatively few were seen off-world, but they refused to be parted from their humans even if those humans chose space-going careers, and the Lords of Admiralty had caved in on that point almost a hundred and fifty Manticoran years before. 'Cats rated a point-eight-three on the sentience scale, slightly above Beowulf's gremlins or Old Earth's dolphins, and they were empaths. Even now, no one had the least idea how their empathic links worked, but separating one from its chosen companion caused it intense pain, and it had been established early on that those favored by a 'cat were measurably more stable than those without. Besides, Crown Princess Adrienne had been adopted by a 'cat on a state visit to Sphinx. When Queen Adrienne of Manticore expressed her displeasure twelve years later at efforts to separate officers in her navy from their companions, the Admiralty found itself with no option but to grant a special exemption from its draconian "no pets" policy.

Honor was glad of it, though she'd been afraid it would be impossible to find time to spend with Nimitz when she entered the Academy. She'd known going in that those forty-five endless months on Saganami Island were deliberately planned to leave even midshipmen without 'cats too few hours to do everything they had to do. But while Academy instructors might suck their teeth and grumble when a plebe turned up with one of the rare 'cats, they recognized natural forces for which allowances must be made when they saw one. Besides, even the most "domesticated" 'cat retained the independence (and indestructibility) of his cousins in the wild, and Nimitz had seemed perfectly aware of the pressure she faced. All he needed was a little grooming, an occasional wrestling bout, a perch on her shoulder or lap while she pored over the book chips and to sleep curled neatly up on her pillow, and he was happy. Not that he'd been above looking mournful and pitiful to extort tidbits and petting from any unfortunate who crossed his path. Even Chief MacDougal, the terror of the first-form middies, had succumbed, carrying a suitable stash of the celery stalks the otherwise carnivorous treecats craved and sneaking them to Nimitz when he thought no one was looking. And, Honor reflected wryly, running Ms. Midshipman Harrington ragged to compensate for his weakness.

Her thoughts had carried her through the arrival gate to the concourse, and she looked about until she found the color-coded guide strip to the personnel tubes. She followed it, unburdened by any baggage, for she had none. All her meager personal possessions had been freighted up this morning, whisked away by stewards at the Advanced Tactical Course facility almost before she'd had time to pack.

She frowned a bit at that thought while she punched up a tube capsule. All the scramble to get her here seemed out of character for a navy that preferred to do things in an orderly fashion. When she'd been given Hawkwing, she'd known two months in advance; this time, she'd been literally snatched out of the ATC graduation ceremonies and hustled off to Admiral Courvosier's office with no warning at all.

The capsule arrived, and she stepped into it, still frowning and rubbing gently at the tip of her nose. Nimitz roused to lift his chin from the top of her beret and nipped her ear with the scolding tug he saved for the unfortunately frequent moments when his companion worried. Honor clicked her teeth gently at him and reached up to scratch his chest, but she didn't stop worrying, and he sighed in exasperation.

Now why, she wondered, was she so certain Courvosier had deliberately bustled her out of his office and off to her new assignment? The admiral was a bland-faced, cherubic little gnome of a man with a bent for creating demonic tac problems, and she'd known him for years. He'd been her Fourth Form Tactics instructor at the Academy, the one who'd recognized an inborn instinct and honed it into something she could command at will, not something that came and went. He'd spent hours working with her in private when other instructors worried about her basic math scores and, in a very real sense, had saved her career before it had actually begun, yet this time there'd been something almost evasive about him. She knew his congratulations and satisfied pride in her had been real, but she couldn't shake the impression that there'd been something else, as well. Ostensibly, the rush was all because of the need to get her to Hephaestus to shepherd her new ship through its refit in time for the upcoming Fleet exercise, yet HMS Fearless was only a single light cruiser, when all was said. It seemed unlikely her absence would critically shift the balance in maneuvers planned to exercise the entire Home Fleet!

No, something was definitely up, and she wished fervently that she'd had time for a full download before catching the shuttle. But at least all the rush had kept her from worrying herself into a swivet the way she had before taking Hawkwing over, and Lieutenant Commander McKeon, her new exec, had served on Fearless for almost two years, first as tactical officer and then as exec. He should be able to bring her up to speed on the refit Courvosier had been so oddly reluctant to discuss.

She shrugged and punched her destination into the capsule's routing panel, then set down her briefcase and resigned herself as it flashed away down the counter-grav tubeway. Despite a peak speed of well over seven hundred kilometers per hour, the capsule trip would take over fifteen minutes—assuming she was lucky enough not to hit too many stops en route.

The deck shivered gently underfoot. Few would have detected the tiny bobble as one quadrant of Hephaestus's gravity generators handed the tube off to another, but Honor noticed it. Not consciously, perhaps, but that minute quiver was part of a world which had become more real to her than the deep blue skies and chill winds of her childhood. It was like her own heartbeat, one of the tiny, uncountable stimuli that told her—instantly and completely—what was happening around her.

She watched the tube map display, shaking off thoughts of evasive admirals and other puzzles as her eyes tracked the blinking cursor of her capsule across it. Her hand rose to press the crispness of her orders once more, and she paused, almost surprised as she looked away from the map and glimpsed her reflection in the capsule's polished wall.

The face that gazed back should have looked different, reflecting the monumental change in her status, and it didn't. It was still all sharply defined planes and angles dominated by a straight, patrician nose (which, in her opinion, was the only remotely patrician thing about her) and devoid of the least trace of cosmetics. Honor had been told (once) that her face had "a severe elegance." She didn't know about that, but the idea was certainly better than the dread, "My, isn't she, um, healthy looking!" Not that "healthy" wasn't accurate, however depressing it might sound. She looked trim and fit in the RMN's black and gold, courtesy of her 1.35-gravity homeworld and a rigorous exercise regimen, and that, she thought, critically, was about the best she had to say about herself.

Most of the Navy's female officers had chosen to adopt the current planet-side fashion of long hair, often elaborately dressed and arranged, but Honor had decided long ago there was no point trying to make herself something she was not. Her hair-style was practical, with no pretensions to glamour. It was clipped short to accommodate vac helmets and bouts of zero-gee, and if its two-centimeter strands had a stubborn tendency to curl, it was neither blond, nor red, nor even black, just a highly practical, completely unspectacular dark brown. Her eyes were even darker, and she'd always thought their hint of an almond shape, inherited from her mother, made them look out of place in her strong-boned face, almost as if they'd been added as an afterthought. Their darkness made her pale complexion seem still paler, and her chin was too strong below her firm-lipped mouth. No, she decided once more, with a familiar shade of regret, it was a serviceable enough face, but there was no use pretending anyone would ever accuse it of radiant beauty ... darn it.

She grinned again, feeling the bubble of delight pushing her worries aside, and her reflection grinned back. It made her look like an urchin gloating over a hidden bag of candy, and she took herself firmly to task for the remainder of the trip, concentrating on a new CO's responsibility to look cool and collected, but it was hard. She'd done well to make commander so soon even with the Fleet's steady growth in the face of the Havenite threat, for the life-extending prolong process made for long careers. The Navy was well-supplied with senior officers, despite its expansion, and she came of yeoman stock, without the high-placed relatives or friends to nudge a naval career along. She'd known and accepted from the start that those with less competence but more exalted bloodlines would race past her. Well, they had, but she'd made it at last. A cruiser command, the dream of every officer worth her salt! So what if Fearless was twice her own age and little larger than a modern destroyer? She was still a cruiser, and cruisers were the Manticoran Navy's eyes and ears, its escorts and its raiders, the stuff of independent commands and opportunity.

And responsibility. That thought let her banish the grin at last, because if independent command was what every good officer craved, a captain all alone in the big dark had no one to appeal to. No one to take the credit or share the blame, for she was all alone, the final arbiter of her ship's fate and the direct, personal representative of her queen and kingdom, and if she failed that trust no power in the galaxy could save her.

The personnel capsule ghosted to a stop, and she stepped out into the spacious gallery of the spacedock, brown eyes hungry as they swept over her new command at last. HMS Fearless floated in her mooring beyond the tough, thick wall of armorplast, lean and sleek even under the clutter of work platforms and access tubes, and the pendant number "CL-56" stood out against the white hull just behind her forward impeller nodes. Yard mechs swarmed over her in the dock's vacuum, supervised by vacsuited humans, but most of the work seemed to be concentrated on the broadside weapon bays.

Honor stood motionless, watching through the armorplast, feeling Nimitz rise straight and tall on her shoulder to join her perusal, and an eyebrow quirked. Admiral Courvosier had mentioned that Fearless was undergoing a major refit, but what was going on out there seemed a bit more major than she'd anticipated. Which, coupled with his deliberate lack of detail, suggested something very special was in the wind, though Honor still couldn't imagine what could be important enough to turn the admiral all mysterious on her. Nor did it matter very much to her as she drank up her new command—her new command!—with avid eyes.

She never knew exactly how long she stood there before she managed to tear her attention away at last and head for the crew tube. The two Marine sentries stood at parade rest, watching her approach, then snapped to attention as she reached them.

She handed over her ID and watched approvingly as the senior man, a corporal, scrutinized it. They knew who she was, of course, unless the grapevine had died a sudden and unexpected death. Even if they hadn't, only one member of any ship's company was permitted the coveted white beret. But neither displayed the least awareness that their new mistress after God had arrived. The corporal handed back her ID folio with a salute, and she returned it and walked past them into the access tube.

She didn't look back, but the bulkhead mirror at the tube's first bend, intended to warn of oncoming traffic coming round the corner, let her watch the sentries as the corporal keyed his wrist com to alert the command deck that the new captain was on her way.

The scarlet band of a zero-gee warning slashed the access tube deck before her, and she felt Nimitz's claws sink deeper into her shoulder pad as she stepped over it. She launched herself into the graceful swim of free-fall as she passed out of Hephaestus's artificial gravity, and her pulse raced with quite unbecoming speed as she eeled down the passage. Another two minutes, she told herself. Only another two minutes.

Lieutenant Commander Alistair McKeon twitched his tunic straight and smothered a flare of annoyance as he stood by the entry port. He'd been buried in the bowels of a vivisected fire control station when the message came in. There'd been no time to shower or change into a fresh uniform, and he felt the sweat staining his blouse under his hastily donned tunic, but at least Corporal Levine's message had given him enough warning to collect the side party. Formal courtesies weren't strictly required from a ship in yard hands, but McKeon would take no chance of irritating a new captain. Besides, Fearless had a reputation to maintain, and—

His spine straightened, and a spasm of something very like pain went through him as his new captain rounded the tube's final bend. Her white beret gleamed under the lights, and he felt his face stiffen as he saw the sleek, cream-and-gray shape riding her shoulder. He hadn't known she had a treecat, and he smothered a fresh spurt of irrational resentment at the sight.

Commander Harrington floated easily down the last few meters of tube, then spun in midair and caught the final, scarlet-hued grab bar that marked the edge of Fearless's internal grav field. She crossed the interface like a gymnast dismounting from the rings to land lightly before him, and McKeon's sense of personal injury grew perversely stronger as he realized how little justice the photo in her personnel jacket had done her. Her triangular face had looked stern and forbidding, almost cold, in the file imagery, especially framed in the dark fuzz of her close-cropped hair, but the pictures had lied. They hadn't captured the life and vitality, the sharp-edged attractiveness. No one would ever call Commander Harrington "pretty," he thought, but she had something far more important. Those clean-cut, strong features and huge, dark brown eyes—exotically angular and sparkling with barely restrained delight despite her formal expression—discounted such ephemeral concepts as "pretty." She was herself, unique, impossible to confuse with anyone else, and that only made it worse.

McKeon met her scrutiny with a stolid expression and fought to suppress his confused, bitter resentment. He saluted sharply, the side party came to attention, and the bosun's calls shrilled. All activity stilled around the entry port, and her hand came up in an answering salute.

"Permission to come aboard?" Her voice was a cool, clear soprano, surprisingly light in a woman her size, for she easily matched McKeon's own hundred and eighty centimeters.

"Permission granted," he replied. It was a formality, but a very real one. Until she officially assumed command, Harrington was no more than a visitor aboard McKeon's ship.

"Thank you," she said, and stepped aboard as he stood back to clear the hatch.

He watched her chocolate-dark eyes sweep over the entry port and side party and wondered what she was thinking. Her sculpted face made an excellent mask for her emotions (except for those glowing eyes, he thought sourly), and he hoped his own did the same. It wasn't really fair of him to resent her. A light cruiser simply wasn't a lieutenant commander's billet, but Harrington was almost five years—over eight T-years—younger than he. Not only was she a full commander, not only did the breast of her tunic bear the embroidered gold star denoting a previous hyper-capable command, but she looked young enough to be his daughter. Well, no, not that young, perhaps, but she could have been his niece. Of course, she was second-generation prolong. He'd checked the open portion of her record closely enough to know that, and the anti-aging treatments seemed to be proving even more effective for second— and third-generation recipients. Other parts of her record—like her penchant for unorthodox tactical maneuvers, and the CGM and Monarch's Thanks she'd earned saving lives when HMS Manticore's forward power room exploded—soothed his resentment a bit, but neither they nor knowing why she seemed so youthful could lessen the emotional impact of finding the slot he'd longed for so hopelessly filled by an officer who not only oozed the effortless magnetism he'd always envied in others but also looked as if she'd graduated from the Academy last year. Nor did the bright, unwavering regard the treecat bent upon him make him feel any better.

Harrington completed her inspection of the side party without comment, then turned back to him, and he smothered his resentment and turned to the next, formalized step of his responsibilities.

"May I escort you to the bridge, Ma'am?" he asked, and she nodded.

"Thank you, Commander," she murmured, and he led the way up-ship.

Honor stepped out of the bridge lift and looked around what was about to become her personal domain. The signs of a frenzied refit were evident, and puzzlement stirred afresh as she noted the chaos of tools and parts strewn across her tactical section. Nothing else even seemed disturbed. Darn it, what hadn't Admiral Courvosier told her about her ship?

But that was for the future. For now, she had other things to attend to, and she crossed to the captain's chair, surrounded by its nest of displays and readouts at the center of the bridge. Most of the displays were retracted into their storage positions, and she rested her hand for a moment on the panel concealing the tactical repeater display. She didn't sit down. By long tradition, that chair was barred to any captain before she'd read herself aboard, but she took her place beside it and coaxed Nimitz off her shoulder and onto its far arm, out of the intercom pickup's field. Then she set aside her briefcase, pressed a stud on the near arm, and listened to the clear, musical chime resounding through the ship.

All activity aboard Fearless stopped. Even the handful of visiting civilian techs slid out from under the consoles they were rewiring or crawled up out of the bowels of power rooms and shunting circuits as the all-hands signal sounded. Bulkhead intercom screens flicked to life with Honor's face, and she felt hundreds of eyes as they noted the distinctive white beret and sharpened to catch their first sight of the captain into whose keeping the Lords of Admiralty in their infinite wisdom had committed their lives.

She reached into her tunic, and paper crackled, whispering from every speaker, as she broke the seals and unfolded her orders.

"From Admiral Sir Lucien Cortez, Fifth Space Lord, Royal Manticoran Navy," she read in her crisp, cool voice, "to Commander Honor Harrington, Royal Manticoran Navy, Thirty-Fifth Day, Fourth Month, Year Two Hundred and Eighty After Landing. Madam: You are hereby directed and required to proceed aboard Her Majesty's Starship Fearless, CL-Five-Six, there to take upon yourself the duties and responsibilities of commanding officer in the service of the Crown. Fail not in this charge at your peril. By order of Admiral Sir Edward Janacek, First Lord of Admiralty, Royal Manticoran Navy, for Her Majesty the Queen."

She fell silent and refolded her orders without even glancing at the pickup. For almost five T-centuries, those formal phrases had marked the transfer of command aboard the ships of the Manticoran Navy. They were brief and stilted, but by the simple act of reading them aloud she had placed her crew under her authority, bound them to obey her upon pain of death. The vast majority of them knew nothing at all about her, and she knew equally little about them, and none of that mattered. They had just become her crew, their very lives dependent upon how well she did her job, and an icicle of awareness sang through her as she finished folding the heavy sheet of paper and turned once more to McKeon.

"Mr. Exec," she said formally, "I assume command."

"Captain," he replied with equal formality, "you have command."

"Thank you." She glanced at the duty quartermaster, reading his nameplate from across the bridge. "Make a note in the log, please, Chief Braun," she said, and turned back to the pickup and her watching crew. "I won't take up your time with any formal speeches, people. We have too much to do and too little time to do it in as it stands. Carry on."

She touched the stud again. The intercom screens went blank, and she lowered herself into the comfortable, contoured chair—her chair now. Nimitz swarmed back onto her shoulder with a slightly aggrieved flip of his tail, and she gestured for McKeon to join her.

The tall, heavyset exec crossed the bridge to her while the bustle of work resumed about them. His gray eyes met hers with, she thought, perhaps just an edge of discomfort ... or challenge. The thought surprised her, but he held out his hand in the traditional welcome to a new captain, and his deep voice was level.

"Welcome aboard, Ma'am," he said. "I'm afraid things are a bit of a mess just now, but we're pretty close to on schedule, and the dock master's promised me two more work crews starting next watch."

"Good." Honor returned his handshake, then stood and walked toward the gutted fire control section with him. "I have to admit to a certain amount of puzzlement, though, Mr. McKeon. Admiral Courvosier warned me we were due for a major refit, but he didn't mention any of this." She nodded at the open panels and unraveled circuit runs.

"I'm afraid we didn't have much choice, Ma'am. We could have handled the energy torpedoes with software changes, but the grav lance is basically an engineering system. Tying it into fire control requires direct hardware links to the main tactical system."

"Grav lance?" Honor didn't raise her voice, but McKeon heard the surprise under its cool surface, and it was his turn to raise an eyebrow.

"Yes, Ma'am." He paused. "Didn't anyone mention that to you?"

"No, they didn't." Honor's lips thinned in what might charitably have been called a smile, and she folded her hands deliberately behind her. "How much broadside armament did it cost us?" she asked after a moment.

"All four graser mounts," McKeon replied, and watched her shoulders tighten slightly.

"I see. And you mentioned energy torpedoes, I believe?"

"Yes, Ma'am. The yard's replaced—is replacing, rather—all but two broadside missile tubes with them."

"All but two?" The question was sharper this time, and McKeon hid an edge of bitter amusement. No wonder she sounded upset, if they hadn't even warned her! He'd certainly been upset when he found out what was planned.

"Yes, Ma'am."

"I see," she repeated, and inhaled. "Very well, Exec, what does that leave us?"

"We still have the thirty-centimeter laser mounts, two in each broadside, plus the missile launchers. After refit, we'll have the grav lance and fourteen torpedo generators, as well, and the chase armament is unchanged: two missile tubes and the sixty-centimeter spinal laser."

He watched her closely, and she didn't—quite—wince. Which, he reflected, spoke well for her self-control. Energy torpedoes were quick-firing, destructive, very difficult for point defense to stop... and completely ineffectual against a target protected by a military-grade sidewall. That, obviously, was the reason for the grav lance, yet if a grav lance could (usually) burn out its target's sidewall generators, it was slow-firing and had a very short maximum effective range. But if Captain Harrington was aware of that, she allowed no trace of it to color her voice.

"I see," she said yet again, and gave her head a little toss. "Very well, Mr. McKeon. I'm sure I've taken you away from something more useful than talking to me. Have my things been stowed?"

"Yes, Ma'am. Your steward saw to it."

"In that case, I'll be in my quarters examining the ship's books if you need me. I'd like to invite the officers to dine with me this evening—I see no point in letting introductions interfere with their duties now." She paused, as if reaching for another thought, then looked back at him. "Before then, I'll want to tour the ship and observe the work in progress. Will it be convenient for you to accompany me at fourteen-hundred?"

"Of course, Captain."

"Thank you. I'll see you then." She nodded and left the bridge without a backward glance.

CHAPTER TWO

Honor Harrington sighed, leaned back from the terminal, and pinched the bridge of her nose. No wonder Admiral Courvosier had been so vague about the refit. Her old mentor knew her entirely too well. He'd known exactly how she would have reacted if he'd told her the truth, and he wasn't about to let her blow her first cruiser command in a fit of temper.

She shook herself and rose to stretch, and Nimitz roused to look her way. He started to slither down from the padded rest her new steward had rigged at her request, but she waved him back with the soft sound which told him she had to think. He cocked his head a moment, then "bleeked" quietly at her and settled back down.

She took a quick turn about her cabin. That was one nice thing about Fearless; at less than ninety thousand tons, she might be small by modern standards, but the captain's quarters were downright spacious compared to Hawkwing's. Still small and cramped in planet-side eyes, perhaps, but Honor hadn't applied planetary standards to her living space in years. She even had her own dining compartment, large enough to seat all of her officers for formal occasions, and that was luxury, indeed, aboard a warship.

Not that spaciousness made her feel any better about the ghastly mutilation Hephaestus was wreaking upon her lovely ship.

She paused to adjust the golden plaque on the bulkhead by her desk. There was a fingerprint on the polished alloy, and she felt a familiar, wry self-amusement as she leaned closer to burnish it away with her sleeve. That plaque had accompanied her from ship to ship and planet-side and back for twelve and a half years, and she would have felt lost without it. It was her good luck piece. Her totem. She rubbed a fingertip gently across the long, tapering wing of the sailplane etched into the gold, remembering the day she'd landed to discover she'd set a new Academy record—one that still stood—for combined altitude, duration, and aerobatics, and she smiled.

But the smile faded as she glanced through the open internal hatch into the dining compartment and returned to the depressing present. She sighed again. She wasn't looking forward to that dinner. For that matter, she wasn't looking forward to her tour of the ship, after what she'd found locked away in her computer. The happiness she'd felt such a short time ago had soured, and what should have been two of the more pleasurable rituals of a change of command looked far less inviting now.

She'd told McKeon she meant to study the ship's books, and so she had, but her main attention had been focused on the refit specs and the detailed instructions she'd found in the captain's secure data base. McKeon's description of the alterations was only too accurate, though he hadn't mentioned that in addition to ripping out two-thirds of Fearless's missile tubes, the yard was gutting her magazine space, as well. Missile stowage was always a problem, particularly for smaller starships like light cruisers and destroyers, because an impeller-drive missile simply had to be big. There were limits to how many you could cram aboard, and since they'd decided to reduce Fearless's tubes, they'd seen no reason not to reduce her magazines, as well. After all, it had let them cram in four additional energy torpedo launchers.

She felt her lips trying to curl into a snarl and forced them to smooth as Nimitz chittered a question at her. The treecat's vocal apparatus was woefully unsuited to forming words. That was no problem with other 'cats, since they relied so heavily on their ill-understood telempathic sense for communication, but it left many humans prone to underestimate their intelligence—badly. Honor knew better, and Nimitz was always sensitive to her moods. Indeed, she suspected he knew her better than she knew herself, and she took a moment to scratch the underside of his jaw before she resumed her pacing.

It was all quite simple, she thought. She'd fallen into the clutches of Horrible Hemphill and her crowd, and now it was up to her to make their stupidity look intelligent.

She gritted her teeth. There were two major schools of tactical thought in the RMN: the traditionalists, championed by Admiral Hamish Alexander, and Admiral of the Red Lady Sonja Hemphill's "jeune ecole." Alexander—and, for that matter, Honor—believed the fundamental tactical truths remained true regardless of weapon systems, that it was a matter of fitting new weapons into existing conceptual frameworks with due adjustment for the capabilities they conferred. The jeune ecole believed weapons determined tactics and that technology, properly used, rendered historical analysis irrelevant. And, unfortunately, politics had placed Horrible Hemphill and her panacea merchants in the ascendant just now.

She shook herself and rose to stretch, and Nimitz roused to look her way. He started to slither down from the padded rest her new steward had rigged at her request, but she waved him back with the soft sound which told him she had to think. He cocked his head a moment, then "bleeked" quietly at her and settled back down.

She took a quick turn about her cabin. That was one nice thing about Fearless; at less than ninety thousand tons, she might be small by modern standards, but the captain's quarters were downright spacious compared to Hawkwing's. Still small and cramped in planet-side eyes, perhaps, but Honor hadn't applied planetary standards to her living space in years. She even had her own dining compartment, large enough to seat all of her officers for formal occasions, and that was luxury, indeed, aboard a warship.

Not that spaciousness made her feel any better about the ghastly mutilation Hephaestus was wreaking upon her lovely ship.

She paused to adjust the golden plaque on the bulkhead by her desk. There was a fingerprint on the polished alloy, and she felt a familiar, wry self-amusement as she leaned closer to burnish it away with her sleeve. That plaque had accompanied her from ship to ship and planet-side and back for twelve and a half years, and she would have felt lost without it. It was her good luck piece. Her totem. She rubbed a fingertip gently across the long, tapering wing of the sailplane etched into the gold, remembering the day she'd landed to discover she'd set a new Academy record—one that still stood—for combined altitude, duration, and aerobatics, and she smiled.

But the smile faded as she glanced through the open internal hatch into the dining compartment and returned to the depressing present. She sighed again. She wasn't looking forward to that dinner. For that matter, she wasn't looking forward to her tour of the ship, after what she'd found locked away in her computer. The happiness she'd felt such a short time ago had soured, and what should have been two of the more pleasurable rituals of a change of command looked far less inviting now.

She'd told McKeon she meant to study the ship's books, and so she had, but her main attention had been focused on the refit specs and the detailed instructions she'd found in the captain's secure data base. McKeon's description of the alterations was only too accurate, though he hadn't mentioned that in addition to ripping out two-thirds of Fearless's missile tubes, the yard was gutting her magazine space, as well. Missile stowage was always a problem, particularly for smaller starships like light cruisers and destroyers, because an impeller-drive missile simply had to be big. There were limits to how many you could cram aboard, and since they'd decided to reduce Fearless's tubes, they'd seen no reason not to reduce her magazines, as well. After all, it had let them cram in four additional energy torpedo launchers.

She felt her lips trying to curl into a snarl and forced them to smooth as Nimitz chittered a question at her. The treecat's vocal apparatus was woefully unsuited to forming words. That was no problem with other 'cats, since they relied so heavily on their ill-understood telempathic sense for communication, but it left many humans prone to underestimate their intelligence—badly. Honor knew better, and Nimitz was always sensitive to her moods. Indeed, she suspected he knew her better than she knew herself, and she took a moment to scratch the underside of his jaw before she resumed her pacing.

It was all quite simple, she thought. She'd fallen into the clutches of Horrible Hemphill and her crowd, and now it was up to her to make their stupidity look intelligent.