Страница:

For more than an hour they inched along the corridor, descending gently, while the sides and roof of their tunnel slowly closed in on them until they were easing along a narrow ledge beside the rushing current, the bed of which was a deep vertical cut not more than two meters wide, but some ten meters deep. The roof continued to close down on them, and soon they were moving with difficulty, bent over double, their packs scraping the rock overhead. Le Cagot swore at the pain in his trembling knees as they pushed along the narrow ledge walking in a half-squat that tormented the muscles of their legs.

As the shaft continued to narrow, the same unspoken thought harried them both. Wouldn’t it be a stupid irony if, after their work of preparation and building up supplies, this was all there was? If this sloping shaft came to an end at a swallow down which the river disappeared?

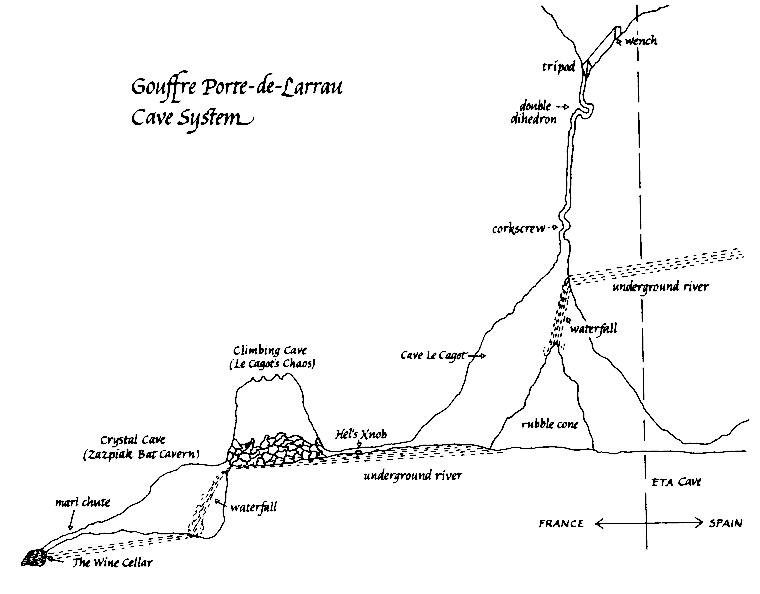

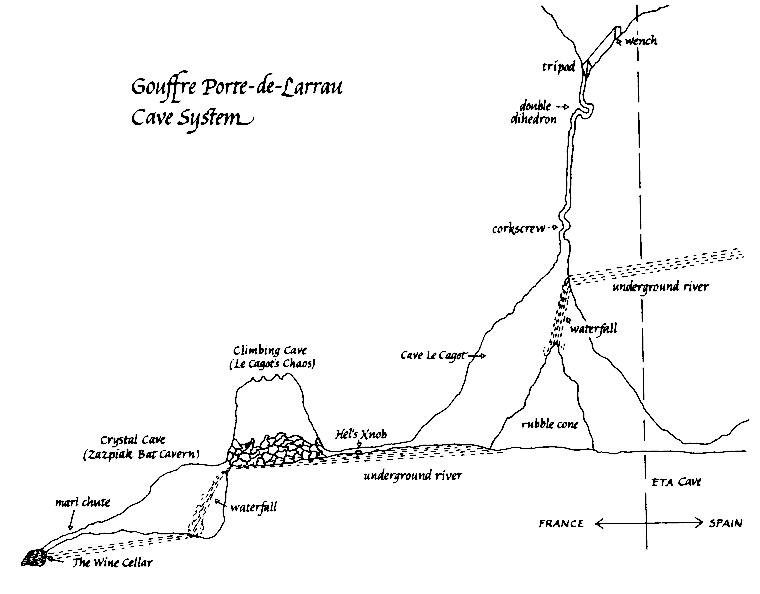

The tunnel began to curve slowly to the left. Then suddenly their narrow ledge was blocked by a knob of rock that protruded out over the gushing stream. It was not possible for Hel to see around the knob, and he could not wade through the riverbed; it was too deep in this narrow cut, and even if it had not been, the possibility of a vertical swallow ahead in the dark was enough to deter him. There were stories of cavers who had stepped into swallows while wading through underground rivers. It was said that they were sucked straight down one hundred, two hundred meters through a roaring column of water at the bottom of which their bodies were churned in some great “giant’s caldron” of boiling foam and rock until they were broken up enough to be washed away. And months afterward bits of equipment and clothing were found in streams and torrents along the narrow valleys of the outfall rivers. These, of course, were campfire tales and mostly lies and exaggerations. But like all folk narratives, they reflected real dreads, and for most cavers in these mountains the nightmare of the sudden swallow is more eroding to the nerves than thoughts of falling while scaling walls, or avalanches, or even being underground during an earthquake. And it is not the thought of drowning that makes the swallow awful, it is the image of being churned to fragments in that boiling giant’s caldron.

“Well?” Le Cagot asked from behind, his voice reverberating in the narrow tunnel. “What do you see?”

“Nothing.”

“That’s reassuring. Are you just going to stand there? I can’t squat here forever like a Béarnais shepherd with the runs!”

“Help me get my pack off.”

In their tight, stooped postures, getting Hel’s pack off was not easy, but once he was free of it he could straighten up a bit. The cut was narrow enough that he could face the stream, set his feet, and let himself fall forward to the wall on the other side. This done, he turned carefully onto his back, his shoulders against one side of the cut, his Vibram boot cleats giving him purchase against the ledge. Wriggling sideward in this pressure stance, using shoulders and palms and the flats of his feet in a traverse chimney climb, he inched along under the projecting knob of rock, the stream roaring only a foot below his buttocks. It was a demanding and chafing move, and he lost some skin from his palms, but he made slow progress.

Le Cagot’s laughter echoed, filling the cave. “Ola! What if it suddenly gets wider, Niko? Maybe you had better lock up there and let me use you like a bridge. That way at least one of us would make it!” And he laughed again.

Mercifully, it didn’t get wider. Once past the knob, the cut narrowed, and the roof rose overhead to a height beyond the beam of Hel’s lamp. He was able to push himself back to the interrupted ledge. He continued to inch along it, still curving to the left. His heart sank when his lamp revealed ahead that the diaclase through which they had been moving came to an abrupt end at an infall of boulders, under which the river gurgled and disappeared.

When he got to the base of the infall raillère and looked around, he could see that he was at the bottom of a great wedge only a couple of meters wide where he stood, but extending up beyond the throw of his light. He rested for a moment, then began a corner climb at the angle of the diaclase and the blocking wall of rubble. Foot— and handholds were many and easy, but the rock was rotten and friable, and each stance had to be tested carefully, each hold tugged to make sure it would not come away in his hand. When he climbed a slow, patient thirty meters, he wriggled into a gap between two giant boulders wedged against one another. Then he was on a flat ledge from which he could see nothing in front or to the sides. He clapped his hands once and listened. The echo was late, hollow, and repeated. He was at the mouth of a big cave.

His return to the knob was rapid; he rappelled down the infall clog on a doubled line which he left in place for their ascent. From his side of the knob he called to Le Cagot, who had retreated a distance back down the tunnel to a narrow place where he could lock himself into a butt-and-heels stance and find some relief from the quivering fatigue of his half-squatting posture.

Le Cagot came back to the knob. “So? Is it a go?”

“There’s a big hole.”

“Fantastic!”

The packs were negotiated on a line around the knob, then Le Cagot repeated Hel’s chimney traverse around that tight bit, complaining bitterly all the while and cursing the knob by the Trumpeting Balls of Joshua and the Two Inhospitable Balls of the Innkeeper.

Because Hel had left a line in place and had cleared out much of the rotten rock, the climb back up the scree clog was not difficult. When they were together on the flat slab just after the crawl between two counterbalanced boulders that was later to be known as the Keyhole, Le Cagot struck off a magnesium flare, and the stygian chaos of that great cavern was seen for the first time in the numberless millennia of its existence.

“By the Burning Balls of the Bush,” Le Cagot said in an awed hush. “A climbing cave!”

It was an ugly sight, but sublime. The raw crucible of creation that was this “climbing” cave muted the egos of these two humanoid insects not quite two meters tall standing on their little flake of stone suspended between the floor of the cave a hundred meters below and the cracked and rotten dome more than a hundred meters above. Most caves feel serene and eternal, but climbing caves are terrible in their organic chaos. Everything here was jagged and fresh; the floor was lost far below in layers of house-size boulders and rubble; and the roof was scarred with fresh infalls. This was a cavern in the throes of creation, an adolescent cave, awkward and unreliable, still in the process of “climbing,” its floor rising from infall and rubble as its roof regularly collapsed. It might soon (twenty thousand years, fifty thousand years) stabilize and become an ordinary cave. Or it might continue to climb up the path of its fractures and faults until it reached the surface, forming in its final infall the funnel-shaped indentation of the classic “dry” gouffre. Of course, the youth and instability of the cave was relative and had to be considered in geological time. The “fresh” scars on the roof could be as young as three years old, or as old as a hundred.

The flare fizzled out, and it was some time before they got their cave eyes back sufficiently to see by the dim light of their helmet lamps. In the spot-dancing black, Hel heard Le Cagot say, “I baptize this cave and christen it. It shall be called Le Cagot Cave!”

From the splattering sound, Hel knew Le Cagot was not wasting water on the baptism. “Won’t that be confusing?” he asked.

“What do you mean?”

“The first cave has the same name.”

“Hm-m-m. That’s true. Well, then, I christen this place Le Cagot’s Chaos! How’s that?”

“Fine.”

“But I haven’t forgotten your contribution to this find, Niko. I have decided to name that nasty outcropping back there—the one we had to traverse—Hel’s Knob. How’s that?”

“I couldn’t ask for more.”

“True. Shall we go on?”

“As soon as I catch up.” Hel knelt over his notebook and compass, and in the light of his helmet lamp scratched down estimates of distance and direction, as he had every hundred or so meters since they left base camp at the rubble heap. After replacing everything in its waterproof packet, he said, “All right. Let’s go.”

Moving cautiously from boulder to boulder, squeezing between cracks and joints, picking their way around the shoulders of massive, toppling rocks the size of barns, they began to cross the Chaos. The Ariadne’s String of the underground river was lost to them beneath layers upon layers of boulders, seeping, winding, bifurcating and rejoining, weaving its thousand threads along the schist floor far below. The recentness of the infalls and the absence of weather erosion that so quickly tames features on the surface combined to produce an insane jumble of precariously balanced slabs and boulders, the crazy canting of which seemed to refute gravity and create a carnival fun house effect in which water appears to run up hill, and what looks level is dangerously slanted. Balance had to be maintained by feel, not by eye, and they had to move by compass because their sense of direction bad been mutilated by their twisting path through the vertigo madness of the Chaos. The problems of pathfinding were quite the opposite of those posed by wandering over a featureless moonscape. It was the confusing abundance of salient features that overloaded and cloyed the memory. And the vast black void overhead pressed down on their subconsciouses, oppressed by that scarred, unseen dome pregnant with infall, one-ten-thousandth part of which could crush them like ants.

Some two hours and five hundred meters later they had crossed enough of the Chaos to be able to see the far end of the cave where the roof sloped down to join the tangle of jagged young fall stone. During the past half-hour, a sound had grown around them, emerging so slowly out of the background ambience of gurgle and hiss far below that they didn’t notice it until they stopped to rest and chart their progress. The thousand strands of the stream below were weaving tighter and tighter together, and the noise that filled the cavern was compounded of a full range of notes from thin cymbal hiss to basso tympany. It was a waterfall, a big waterfall somewhere behind that meeting of roof and rubble that seemed to block off the cave.

For more than an hour, they picked back and forth along the rubble wall, squeezing into crevices and triangular tents formed of slabs weighing tons, but they could find no way through the tangle. There were no boulders at this newer end of the Chaos, only raw young slab, many of which were the size of village frontons, some standing on end, some flat, some tilted at unlikely angles, some jetting out over voids for three-fourths of their length, held up by the cantilevering weight of another slab. And all the while, the rich roar of the waterfall beyond this infall lured them to find a way through.

“Let’s rest and collect ourselves!” Le Cagot shouted over the noise, as he sat on a small fragment of slab, tugged off his pack, and pawed around inside for a meal of hardtack, cheese, and xoritzo. “Aren’t you hungry?”

Hel shook his head. He was scratching away at his notebook, making bold estimates of direction and even vaguer guesses of slope, as the clinometer of his Brunton compass had been useless in the wilderness of the Chaos.

“Could that be the outfall behind the wall?” Le Cagot asked.

“I don’t think so. We’re not much more than halfway to the Torrent of Holçarté, and we must still be a couple of hundred meters too high.”

“And we can’t even get down to the water to dump the dye in. What a nuisance this wall is! What’s worse, we just ran out of cheese. Where are you going?”

Hel had dropped off his pack and was beginning a free climb of the wall. “I’m going to take a look at the tip of the heap.”

“Try a little to your left!”

“Why? Do you see something there?”

“No. But I’m sitting right in the line of your fall, and I’m too comfortable to move.”

They had not given much thought to trying the top of the slab heap because, even if there was a way to squeeze through, it would bring them out directly above the waterfall, and it would probably be impossible to pass through that roaring cascade. But the base and flanks of the clog had produced no way through, so the tip was all that was left.

Half an hour later, Le Cagot heard a sound above him. He tilted back his head to direct the beam of his lamp toward it. Hel was climbing back down in the dark. When he reached the slab, he slumped down to a sitting position, then lay back on his pack, one arm over his face. He was worn out and panting with effort, and the lens of his helmet lamp was cracked from a fall.

“You’re sure you won’t have anything to eat?” Le Cagot asked.

His eyes closed, his chest heaving with great gulps of air, sweat running down his face and chest despite the damp cold of the cave, Hel responded to his companion’s grim sense of humor by making the Basque version of the universal hand language of animosity: he tucked his thumb into his fist and offered it to Le Cagot. Then he let the fist fall and lay there panting. His attempts to swallow were painful, the dryness in his throat was sharp-edged. Le Cagot passed his xahako over, and Hel drank greedily, beginning with the tip touching his teeth, because he had no light, then pulling it farther away and directing the thin jet of wine to the back of his throat by feel. He kept pressure on the sac, swallowing each time the back of his throat filled, drinking for so long that Le Cagot began to worry about his wine.

“Well?” Le Cagot asked grudgingly. “Did you find a way through?”

Hel grinned and nodded.

“Where did you come out?”

“Dead center above the waterfall.”

“Shit!”

“No, I think there’s a way around to the right, down through the spray.”

“Did you try it?”

Hel shrugged and pointed to the broken helmet lens. “But I couldn’t make it alone. I’ll need you to protect me from above. There’s a good belaying stance.”

“You shouldn’t have risked trying. Niko. One of these days you’ll kill yourself, then you’ll be sorry.”

When he had wriggled through the mad network of cracks that brought him out beside Hel on a narrow ledge directly above the roaring waterfall, Le Cagot was exuberant with wonder. It was a long drop, and the mist rose through the windless air, back up the column of water, boiling all about them like a steam bath with a temperature of 40°. All they could see through the mist was the head of the falls below and a few meters of slimy rock to the sides of they ledge. Hel led the way to the right, where the ledge narrowed to a few centimeters, but continued around the shoulder of the cave opening. It was a worn, rounded ledge, obviously a former lip of the waterfall. The cacophonous crash of the falls made sign language their only means of communication as Hel indicated to Le Cagot the “good” belaying stance he had found, an outcrop of rock into which Le Cagot had to squeeze himself with difficulty and pay out the defending line around Hel’s waist as he worked his way down the edge of the falls. The natural line of descent would bring him through the mist, through the column of water, and—it was to be hoped—behind it. Le Cagot grumbled about this “good” stance as he fixed his body into the wedge and drove a covering piton into the limestone above him, complaining that a piton in limestone is largely a psychological decoration.

Hel began his descent, stopping each time he found the coincidence of a foothold for himself and a crack in the rock to drive in a piton and thread his line through the carabiner. Fortunately, the rock was still well-toothed and offered finger— and toeholds; the change in the falls course had been fairly recent, and it had not had time to wear all the ledge smooth. The greatest problem was with the line overhead. By the time he had descended twenty meters and had laced the line through eight carabiners, it took dangerous effort to tug slack against the heavy friction of the soaked rope through so many snap links; the effort of pulling on the line lifted his body partially out of his footholds. And this weakening of his stance occurred, of course, just when Le Cagot was paying out line from above and was, therefore, least able to hold him, should he slip.

He inched down through the sheath of mist until the oily black-and-silver sheet of the waterfall was only a foot from his helmet lamp, and there he paused and collected himself for the diciest moment of the descent.

First he would have to establish a cluster of pitons, so that he could work independently of Le Cagot, who might blindly resist on the line and arrest Hel while he was under the falls, blinded by the shaft of water, feeling for holds he could not see. And he would be taking the weight of the falling water on his back and shoulders. He had to give himself enough line to move all the way through the cascade, because he would not be able to breathe until he was behind it. On the other hand, the more line he gave himself, the greater his drop would be if the water knocked him off. He decided to give himself about three meters of slack. He would have liked more to avoid the possibility of coming to the end of his slack while still under the column of water, but his judgment told him that three meters was the maximum length that would swing him back out of the line of the falls, should he fall and knock himself out for long enough to drown, if he was hanging in the falls.

Hel edged to the face of the metallic, glittering sheet of water until it was only inches away from his face, and soon he began to have the vertigo sensation that the water was standing still, and his body rising through the roar and the mist. He reached into the face of the falls, which split in a heavy, throbbing bracelet around his wrist, and felt around for the deepest handhold he could find. His fingers wriggled their way into a sharp little crack, unseen behind the water. The hold was lower than he would have wished, because he knew the weight of the water on his back would force him down, and the best handhold would have been high, so the weight would have jammed his fingers in even tighter. But it was the only crack he could find, and his shoulder was beginning to tire from the pounding of the water on his outstretched arm. He took several deep breaths, fully exhaling each one because he knew that it is more the buildup of carbon dioxide in the lungs than the lack of oxygen that forces a man to gasp for air. The last breath he took deeply, stretching his diaphragm to its full. Then he let a third of it out, and he swung into the falls.

It was almost comic, and surely anticlimactic.

The sheet of falling water was less than twenty centimeters thick, and the same movement that swung him into it sent him through and behind the cascade, where he found himself on a good ledge below which was a book corner piled with rubble so easy that a healthy child could make the climb down.

It was so obvious a go that, there was no point in testing it, so Hel broke back through the sheet of water and scrambled up to Le Cagot’s perch where, shouting over the din of the falls into Beñat’s ear, their helmets clicking together occasionally, he explained the happy situation. They decided to leave the line in place to facilitate the return, and down they went one after the other, until they were at the base of the rubble-packed book corner.

It was a peculiar phenomenon that, once they were behind the silver-black sheet of the falls, they could speak in almost normal volume, as the curtain of water seemed to block out sound, and it was quieter behind the falls than without. As they descended, the fails slowly broke up as a great quantity of its water spun off in the mist, and the weight of the cascade at the bottom was considerably less than it was above. Its mass was diffused, and passing through it was more like going through a torrential rainfall than a waterfall. They advanced cautiously through the blinding, frigid steam, over a slick rock floor scrubbed clean of rubble. As they pressed on, the mists thinned until they found themselves in the clear dark air, the noise of the falls receding behind them. They paused and looked around. It was beautiful, a diamond cave of more human dimensions than the awful Le Cagot’s Chaos; a tourist cave, far beyond the access capacities of any tourist.

Although it was wasteful, their curiosity impelled them to scratch off another magnesium flare.

Breathtakingly beautiful. Behind them, billowing clouds of mist churning lazily in the suction of the falling water. All around and above them, wet and dripping, the walls were encrusted with aragonite crystals that glittered as Le Cagot moved the flare back and forth. Along the north wall, a frozen waterfall of flowstone oozed down the side and puddled like ossified taffy. To the east, receding and overlapping curtains of calcite drapery, delicate and razor-sharp, seemed to ripple in an unfelt spelean wind. Close to the walls, thickets of slender crystal stalactites pointed down toward stumpy stalagmites, and here and there the forest was dominated by a thick column formed by the union of these patient speleotherns.

They did not speak until the glare sputtered orange and went out, and the glitter of the walls was replaced by dancing dots of light in their eyes as they dilated to accommodate the relatively feeble helmet lamps. Le Cagot’s voice was uncharacteristically hushed when he said, “We shall call this Zazpiak Bat Cave.”

Hel nodded. Zazpiak bat: “Out of seven, let there be one,” the motto of those who sought to unite the seven Basque provinces into a Trans-Pyrenean republic. An impractical dream, neither likely nor desirable, but a useful focus for the activities of men who choose romantic danger over safe boredom, men who are capable of being cruel and stupid, but never small or cowardly. And it was right that the cuckoo-land dream of a Basque nation be represented by a fairyland cave that was all but inaccessible.

He squatted down and made a rough measurement back to the top of the waterfall with his clinometer, then he did a bit of mental arithmetic. “We’re down almost to the level of the Torrent of Holçarté. The outfall can’t be far ahead.”

“Yes,” Le Cagot said, “but where is the river? What have you done with it?”

It was true that the river had disappeared. Broken up by the falls, it had evidently sounded through cracks and fissures and must be running below them somewhere. There were two possibilities. Either it would emerge again within the cave somewhere before them, or the cracks around the base of the waterfall constituted its final swallow before its outfall into the gorge. This latter would be unfortunate, because it would deny them any hope of final conquest by swimming through to the open air and sky. It would also make the long vigil of the Basque lads camped at the outfall pointless.

Le Cagot took the lead as they advanced through Zazpiak Bat Cavern, as he always did when the going was reasonably easy. They both knew that Nicholai was the better rock tactician; it was not necessary for Le Cagot to admit it, or for Hel to accent it. The lead simply changed automatically with the nature of a cave’s features. Hel led through shafts, down faces, around cornices; while Le Cagot led as they entered caves and dramatic features, which he therefore “discovered” and named.

As he led, Le Cagot was testing his voice in the cave, singing one of those whining, atonic Basque songs that demonstrate the race’s ability to withstand aesthetic pain. The song contained that uniquely Basque onomatopoeia that goes beyond imitations of sounds, to imitations of emotional states. In the refrain of Le Cagot’s song, work was being done sloppily (kirrimarra) by a man in confused haste (tarrapatakan).

He stopped singing when he approached the end of the diamond cave and stood before a broad, low-roofed gallery that opened out like a black, toothless grin. Indeed, it held a joke.

Le Cagot directed his lamp down the passage. The slope increased slightly, but it was no more than 15°, and there was enough overhead space for a man to stand erect. It was an avenue, a veritable boulevard! And yet more interesting, it was probably the last feature of the cave system. He stepped forward… and fell with a clatter of gear.

The floor of the passage was thickly coated with clay marl, as slick and filthy as axle grease and flat on his back, Le Cagot was slipping down the incline, not moving very fast at first, but absolutely helpless to arrest his slide. He cursed and pawed around for a hold, but everything was coated with the slimy mess, and there were no boulders or outcroppings to cling to. His struggling did no more than turn him around so that he was going down backward, half-sitting, helpless, furious, and risible. His slide began to pick up speed. From back on the edge of the marl shaft, Hel watched the helmet light grow smaller as it receded, turning slowly like the beam of a lighthouse. There was nothing he could do. The situation was basically comic, but if there was a cliff at the end of the passage…

There was no cliff at the end of the passage. Hel had never known a marl chute at this depth. At a good distance away, perhaps sixty meters, the light stopped moving. There was no sound, no call for help. Hel feared that Le Cagot had been bashed against the side of the passage and was lying there broken up.

Then came a sound up through the passage, Le Cagot’s voice roaring with fury and outrage, the words indistinct because of the covering reverberations, but carrying the tonalities of wounded dignity. One phrase in the echoing outpour was decipherable: “…by the Perforated Balls of Saint Sebastian!”

So Le Cagot was unhurt. The situation might even be funny, were it not that their only coil of rope had gone down with him, and not even that ox of Urt could throw a coil of line sixty meters uphill.

Hel blew out a deep sigh. He would have to go back through Zazpiak Bat Cavern, through the base of the waterfall, up the rubble corner, back out through the falls, and up that dicy climb through icy mists to retrieve the line they had left in place to ease their retreat. The thought of it made him weary.

But… He tugged off his pack. No point carrying it with him. He called down the marl passage, spacing his words out so they would be understood through the muffling reverberations.

“I’m… going… after… line!”

The dot of light below moved. Le Cagot was standing up. “Why… don’t… you… do… that!” came the call back. Suddenly the light disappeared, and there was the echoing sound of a splash, followed by a medley of angry roaring, scrambling, sputtering, and swearing. Then the light reappeared.

Hel’s laughter filled both the passage and the cave. Le Cagot had evidently fallen into the river which must have come back to the surface down there. What a beginner’s stunt!

Le Cagot’s voice echoed back up the marl chute: “I… may… kill… you… when… you… get… down… here!”

Hel laughed again and set off back to the lip of the falls.

Three-quarters of an hour later, he was back at the head of the marl chute, fixing the line into a healthy crack by means of a choke nut.

Hel tried at first to take a rope-controlled glissade on his feet, but that was not on. The marl was too slimy. Almost at once he found himself on his butt, slipping down feet first, a gooey prow bone of black marl building up at his crotch and oozing back over his hip. It was nasty stuff, an ignoble obstacle, formidable enough but lacking the clean dignity of a cave’s good challenges: cliffs and rotten rock, vertical shafts and dicy siphons. It was a mosquito of a problem, stupid and irritating, the overcoming of which brought no glory. Marl chutes are despised by all cavers who have mucked about in them.

When Hel glissed silently to his side, Le Cagot was sitting on a smooth slab, finishing off a hardtack biscuit and a cut of xoritzo. He ignored Hel’s approach, still sulky over his own undignified descent, and dripping wet from his dunking.

Hel looked around. No doubt of it, this was the end of the cave system. The chamber was the size of a small house, or of one of the reception rooms of his château at Etchebar. Evidently, it was sometimes filled with water—the walls were smooth, and the floor was free of rubble. The slab on which Le Cagot was taking his lunch covered two-thirds of the floor, and in the distant corner there was a neat cubic depression about five meters on each edge—a regular “wine cellar” of a sump constituting the lowest point of the entire cave system. Hel went to the edge of the Wine Cellar and directed his beam down. The sides were smooth, but it looked to be a fairly easy corner climb, and he wondered why Le Cagot hadn’t climbed down to be the first man to the end of the cave.

“I was saving it for you,” Le Cagot explained.

“An impulse toward fair play?”

“Exactly.”

There was something very wrong here. Basque to the bone though he was, Le Cagot had been educated in France, and the concept of fair play is totally alien to the mentality of the French, a people who have produced generations of aristocrats, but not a single gentleman; a culture in which the legal substitutes for the fair; a language in which the only word for fair play is the borrowed English.

Still, there was no point in standing there and letting the floor of that final Wine Cellar go virgin. Hel looked down, scanning for the best holds.

…Wait a minute! That splash. Le Cagot had fallen into water. Where was it?

Hel carefully lowered his boot into the Wine Cellar. A few centimeters down, it broke the surface of a pool so clear it appeared to be air. The features of the rock below were so sharp that no one would suspect they were under water.

“You bastard,” Hel whispered. Then he laughed. “And you climbed right down into it, didn’t you?”

The instant he pulled up his boot, the ripples disappeared from the surface, sucked flat by a strong siphon action below. Hel knelt at the side of the sump and examined it with fascination. The surface was not still at all; it was drawn tight and smooth by the powerful current below. Indeed, it bowed slightly, and when he put in his finger, there was a strong tug and a wake of eddy patterns behind it. He could make out a triangular opening down at the bottom of the sump which must be the outflow of the river. He had met trick pools like these before in caves, pools into which the water entered without bubbles to mark its current, the water so purified of those minerals and microorganisms that give it its tint of color.

Hel examined the walls of their small chamber for signs of water line. Obviously, the outflow through that triangular pipe down there had to be fairly constant, while the volume of the underground river varied with rainfall and seep water. This whole chamber, and that marl chute behind them acted as a kind of cistern that accepted the difference between inflow and outflow. That would account for marl appearing this far underground. There were doubtless times when this chamber in which they sat was full of water which backed up through the long chute. Indeed, upon rare occasions of heavy rain, the waterfall back there probably dropped into a shallow lake that filled the floor of Zazpiak Cavern. That would explain the stubbiness of the stalagmites in that diamond cave. If they had arrived at some other time, say a week after heavy rains had seeped down, they might have found their journey ending in Zazpiak Cavern. They had planned all along to consider a scuba exploration to the outfall in some future run, should the timing on the dye test prove practicable. But if they had been stopped by a shallow lake in the cavern above, it would have been unlikely that Hel would ever find that marl chute under water, swim all the way down it, locate this Wine Cellar sump, pass out through the triangular opening, and make it through that powerful current to the outfall. They were lucky to have made their descent after a long dry spell.

“Well?” Le Cagot said, looking at his watch. “Shall we drop the dye in?”

“What time is it?”

“A little before eleven.”

“Let’s wait for straight up. It’ll make calculation easier.” Hel looked down through the invisible pane of water. It was difficult to believe that there at the bottom, among those clear features of the floor, a current of great force was rushing, sucking. “I wish I knew two things,” he said.

“Only two?”

“I wish I knew how fast that water was moving. And I wish I knew if that triangular pipe was clear.”

“Let’s say we get a good timing—say ten minutes—are you going to try swimming it next time we come down?”

“Of course. Even with fifteen minutes.”

Le Cagot shook his head. “That’s a lot of line, Niko. Fifteen minutes through a pipe like that is a lot of line for me to haul you back against the current if you run into trouble. No, I don’t think so. Ten minutes is maximum. If it’s longer than that, we should let it go. It’s not so bad to leave a few of Nature’s mysteries virgin.”

Le Cagot was right, of course.

“You have any bread in your pack?” Hel asked.

“What are you going to do?”

“Cast it upon the waters.”

Le Cagot tossed over a cut of his flute baguette; Hel set it gently on the surface of the sump water and watched its motion. It sank slowly, seeming to fall in slow motion through clear air, as it pulsed and vibrated with unseen eddies. It was an unreal and eerie sight, and the two men watched it fascinated. Then suddenly, like magic, it was gone. It had touched the current down there and had been snatched into the pipe faster than the eye could follow.

Le Cagot whistled under his breath. “I don’t know, Niko. That looks like a bad thing.”

But already Hel was making preliminary decisions. He would have to enter the pipe feet first with no fins because it would be suicidal to rush head first through that triangular pipe, in case be met a choking boulder inside there. That could be a nasty knock. Then too, he would want to be head first coming out if it was not a go, so he could help Le Cagot’s weight on the safety line by pushing with his feet.

“I don’t like it, Niko. That little hole there could kill your ass and, what is worse, reduce the number of my admirers by one. And remember, dying is a serious business. If a man dies with a sin on his soul, he goes to Spain.”

“We have a couple of weeks to think it over. After we get out, we’ll talk about it and see if it’s worth dragging scuba gear down here. For all we know, the dye test will tell us the pipe’s too long for a try. What time is it?”

“Coming up to the hour.”

“Let’s drop off the dye then.”

The fluorescein dye they had carried down was in two-kilo bags. Hel tugged them out of their packs, and Le Cagot cut off the corners and lined them along the edge of the Wine Cellar sump. When the second hand swept to twelve, they pushed them all in. Bright green smoke seeped from the cuts as the bags dropped through the crystal water. Two of them disappeared instantly through the triangular pipe, but the other two lay on the bottom, their smoking streams of color rushing horizontally toward the pipe until the nearly empty bags were snatched away by the current. Three seconds later, the water was clear and still again.

“Niko? I have decided to christen this little pool Le Cagot’s Soul.”

“Oh?”

“Yes. Because it is clear and pure and lucid.”

“And treacherous and dangerous?”

“You know, Niko, I begin to suspect that you are a man of prose. It is a blemish in you.”

“No one’s perfect.”

“Speak for yourself.”

The return to the base of the rubble cone was relatively quick. Their newly discovered cave system was, after all, a clean and easy one with no long crawls through tight passages and around breakdowns, and no pits to contend with, because the underground river ran along the surface of a hard schist bed.

The Basque boys dozing up at the winch were surprised to hear their voices over the headsets of the field telephones hours before they had expected them.

“We have a surprise for you,” one lad said over the line.

“What’s that?” Le Cagot asked.

“Wait till you get up and see for yourself.”

The long haul up from the tip of the rubble cone to the first corkscrew shaft was draining for each of the men. The strain on the diaphragm and chest from banging in a parachute harness is very great, and men have been known to suffocate from it. It was such a constriction of the diaphragm that caused Christ’s death on the cross—a fact the aptness of which did not escape Le Cagot’s notice and comment.

To, shorten the torture of hanging in the straps and struggling to breathe, the lads at the low-geared winch pedaled heroically until the man below could take a purchase within the corkscrew and rest for a while, getting some oxygen back into his blood.

Hel came up last, leaving the bulk of their gear below for future explorations. After he negotiated the double dihedron with a slack cable, it was a short straight haul up to the cone point of the gouffre, and he emerged from blinding blackness… into blinding white.

While they had been below, an uncommon atmospheric inversion had seeped into the mountains, creating that most dangerous of weather phenomena: a whiteout.

For several days, Hel and his mountaineer companions had known that conditions were developing toward a whiteout because, like all Basques from Haute Soule, they were constantly if subliminally attuned to the weather patterns that could be read in the eloquent Basque sky as the dominant winds circled in their ancient and regular boxing of the compass. First Ipharra, the north wind, sweeps the sky clear of clouds and brings a cold, greenish-blue light to the Basque sky, tinting and hazing the distant mountains. Ipharra weather is brief, for soon the wind swings to the east and becomes the cool Iduzki-haizea, “the sunny wind,” which rises each morning and falls at sunset, producing the paradox of cool afternoons with warm evenings. The atmosphere is both moist and clear, making the contours of the countryside sharp, particularly when the sun is low and its oblique light picks out the textures of bush and tree; but the moisture blues and blurs details on the distant mountains, softening their outlines, smudging the border between mountain and sky. Then one morning one looks out to find that the atmosphere has become crystalline, and distant mountains have lost their blue haze, have closed in around the valley, their razor outlines acid-etched into the ardent blue of the sky. This is the time of Hego-churia, “the white southeast wind.” In autumn, Hego-churia often dominates the weather for weeks on end, bringing the Pays Basque’s grandest season. With a kind of karma justice, the glory of Hego-churia is followed by the fury of Haize-hegoa, the bone-dry south wind that roars around the flanks of the mountains, crashing shutters in the villages, ripping roof tiles off, cracking weak trees, scudding blinding swirls of dust along the ground. In true Basque fashion, paradox being the normal way of things, this dangerous south wind is warm velvet to the touch. Even while it roars down valleys and clutches at houses all through the night, the stars remain sharp and close overhead. It is a capricious wind, suddenly relenting into silences that ring like the silence after a gunshot, then returning with full fury, destroying the things that man makes, testing and shaping the things that God makes, shortening tempers and fraying nerve ends with its constant screaming around corners and reedy moaning down chimneys. Because the Haize-hegoa is capricious and dangerous, beautiful and pitiless, nerve-racking and sensual, it is often used in Basque sayings as a symbol of Woman. Finally spent, the south wind veers around to the west, bringing rain and heavy clouds that billow gray in their bellies but glisten silver around the edges. There is—as there always is in Basqueland—an old saying to cover the phenomenon: Hegoak hegala urean du, “The south wind flies with one wing in the water.” The rain of the southwest wind falls plump and vertically and is good for the land. But it veers again and brings the Haize-belza, “the black wind,” with its streaming squalls that drive rain horizontally, making umbrellas useless, indeed, comically treacherous. Then one evening, unexpectedly, the sky lightens and the surface wind falls off, although high altitude streams continue to rush cloud layers overhead, tugging them apart into wisps. As the sun sets, chimerical archipelagos of fleece are scudded southward where they pile up in gold and russet against the flanks of the high mountains.

This beauty lasts only one evening. The next morning brings the greenish light of Ipharra. The north wind has returned. The cycle begins again.

Although the winds regularly cycle around the compass, each with its distinctive personality, it is not possible to say that Basque weather is predictable; for in some years there are three or four such cycles, and in other years only one. Also, within the context of each prevailing wind there are vagaries of force and longevity. Indeed, sometimes the wind turns through a complete personality during a night, and the next morning it seems that one of the dominant phases has been skipped. Too, there are the balance times between the dominance of two winds, when neither is strong enough to dictate. At such times, the mountain Basque say, “There is no weather today.”

And when there is no weather, no motion of wind in the mountains, then sometimes comes the beautiful killer: the whiteout. Thick blankets of mist develop, dazzling white because they are lighted by the brilliant sun above the layer. Eye-stinging, impenetrable, so dense and bright that the extended hand is a faint ghost and the feet are lost in milky glare, a major whiteout produces conditions more dangerous than simple blindness; it produces vertigo and sensory inversion. A man experienced in the ways of the Basque mountains can move through the darkest night. His blindness triggers off a compensating heightening of other senses; the movement of wind on his cheek tells him that he is approaching an obstacle; small sounds of rolling pebbles give him the slant of the ground and the distance below. And the black is never complete; there is always some skyglow picked up by widely dilated eyes.

But in a whiteout, none of these compensating sensory reactions obtains. The dumb nerves of the eyes, flooded and stung with light, persist in telling the central nervous system that they can see, and the hearing and tactile systems relax, slumber. There is no wind to offer subtle indications of distance, for wind and whiteout cannot coexist. And all sound is perfidious, for it carries far and crisp through the moisture-laden air, but seems to come from all directions at once, like sound under water.

As the shaft continued to narrow, the same unspoken thought harried them both. Wouldn’t it be a stupid irony if, after their work of preparation and building up supplies, this was all there was? If this sloping shaft came to an end at a swallow down which the river disappeared?

The tunnel began to curve slowly to the left. Then suddenly their narrow ledge was blocked by a knob of rock that protruded out over the gushing stream. It was not possible for Hel to see around the knob, and he could not wade through the riverbed; it was too deep in this narrow cut, and even if it had not been, the possibility of a vertical swallow ahead in the dark was enough to deter him. There were stories of cavers who had stepped into swallows while wading through underground rivers. It was said that they were sucked straight down one hundred, two hundred meters through a roaring column of water at the bottom of which their bodies were churned in some great “giant’s caldron” of boiling foam and rock until they were broken up enough to be washed away. And months afterward bits of equipment and clothing were found in streams and torrents along the narrow valleys of the outfall rivers. These, of course, were campfire tales and mostly lies and exaggerations. But like all folk narratives, they reflected real dreads, and for most cavers in these mountains the nightmare of the sudden swallow is more eroding to the nerves than thoughts of falling while scaling walls, or avalanches, or even being underground during an earthquake. And it is not the thought of drowning that makes the swallow awful, it is the image of being churned to fragments in that boiling giant’s caldron.

“Well?” Le Cagot asked from behind, his voice reverberating in the narrow tunnel. “What do you see?”

“Nothing.”

“That’s reassuring. Are you just going to stand there? I can’t squat here forever like a Béarnais shepherd with the runs!”

“Help me get my pack off.”

In their tight, stooped postures, getting Hel’s pack off was not easy, but once he was free of it he could straighten up a bit. The cut was narrow enough that he could face the stream, set his feet, and let himself fall forward to the wall on the other side. This done, he turned carefully onto his back, his shoulders against one side of the cut, his Vibram boot cleats giving him purchase against the ledge. Wriggling sideward in this pressure stance, using shoulders and palms and the flats of his feet in a traverse chimney climb, he inched along under the projecting knob of rock, the stream roaring only a foot below his buttocks. It was a demanding and chafing move, and he lost some skin from his palms, but he made slow progress.

Le Cagot’s laughter echoed, filling the cave. “Ola! What if it suddenly gets wider, Niko? Maybe you had better lock up there and let me use you like a bridge. That way at least one of us would make it!” And he laughed again.

Mercifully, it didn’t get wider. Once past the knob, the cut narrowed, and the roof rose overhead to a height beyond the beam of Hel’s lamp. He was able to push himself back to the interrupted ledge. He continued to inch along it, still curving to the left. His heart sank when his lamp revealed ahead that the diaclase through which they had been moving came to an abrupt end at an infall of boulders, under which the river gurgled and disappeared.

When he got to the base of the infall raillère and looked around, he could see that he was at the bottom of a great wedge only a couple of meters wide where he stood, but extending up beyond the throw of his light. He rested for a moment, then began a corner climb at the angle of the diaclase and the blocking wall of rubble. Foot— and handholds were many and easy, but the rock was rotten and friable, and each stance had to be tested carefully, each hold tugged to make sure it would not come away in his hand. When he climbed a slow, patient thirty meters, he wriggled into a gap between two giant boulders wedged against one another. Then he was on a flat ledge from which he could see nothing in front or to the sides. He clapped his hands once and listened. The echo was late, hollow, and repeated. He was at the mouth of a big cave.

His return to the knob was rapid; he rappelled down the infall clog on a doubled line which he left in place for their ascent. From his side of the knob he called to Le Cagot, who had retreated a distance back down the tunnel to a narrow place where he could lock himself into a butt-and-heels stance and find some relief from the quivering fatigue of his half-squatting posture.

Le Cagot came back to the knob. “So? Is it a go?”

“There’s a big hole.”

“Fantastic!”

The packs were negotiated on a line around the knob, then Le Cagot repeated Hel’s chimney traverse around that tight bit, complaining bitterly all the while and cursing the knob by the Trumpeting Balls of Joshua and the Two Inhospitable Balls of the Innkeeper.

Because Hel had left a line in place and had cleared out much of the rotten rock, the climb back up the scree clog was not difficult. When they were together on the flat slab just after the crawl between two counterbalanced boulders that was later to be known as the Keyhole, Le Cagot struck off a magnesium flare, and the stygian chaos of that great cavern was seen for the first time in the numberless millennia of its existence.

“By the Burning Balls of the Bush,” Le Cagot said in an awed hush. “A climbing cave!”

It was an ugly sight, but sublime. The raw crucible of creation that was this “climbing” cave muted the egos of these two humanoid insects not quite two meters tall standing on their little flake of stone suspended between the floor of the cave a hundred meters below and the cracked and rotten dome more than a hundred meters above. Most caves feel serene and eternal, but climbing caves are terrible in their organic chaos. Everything here was jagged and fresh; the floor was lost far below in layers of house-size boulders and rubble; and the roof was scarred with fresh infalls. This was a cavern in the throes of creation, an adolescent cave, awkward and unreliable, still in the process of “climbing,” its floor rising from infall and rubble as its roof regularly collapsed. It might soon (twenty thousand years, fifty thousand years) stabilize and become an ordinary cave. Or it might continue to climb up the path of its fractures and faults until it reached the surface, forming in its final infall the funnel-shaped indentation of the classic “dry” gouffre. Of course, the youth and instability of the cave was relative and had to be considered in geological time. The “fresh” scars on the roof could be as young as three years old, or as old as a hundred.

The flare fizzled out, and it was some time before they got their cave eyes back sufficiently to see by the dim light of their helmet lamps. In the spot-dancing black, Hel heard Le Cagot say, “I baptize this cave and christen it. It shall be called Le Cagot Cave!”

From the splattering sound, Hel knew Le Cagot was not wasting water on the baptism. “Won’t that be confusing?” he asked.

“What do you mean?”

“The first cave has the same name.”

“Hm-m-m. That’s true. Well, then, I christen this place Le Cagot’s Chaos! How’s that?”

“Fine.”

“But I haven’t forgotten your contribution to this find, Niko. I have decided to name that nasty outcropping back there—the one we had to traverse—Hel’s Knob. How’s that?”

“I couldn’t ask for more.”

“True. Shall we go on?”

“As soon as I catch up.” Hel knelt over his notebook and compass, and in the light of his helmet lamp scratched down estimates of distance and direction, as he had every hundred or so meters since they left base camp at the rubble heap. After replacing everything in its waterproof packet, he said, “All right. Let’s go.”

Moving cautiously from boulder to boulder, squeezing between cracks and joints, picking their way around the shoulders of massive, toppling rocks the size of barns, they began to cross the Chaos. The Ariadne’s String of the underground river was lost to them beneath layers upon layers of boulders, seeping, winding, bifurcating and rejoining, weaving its thousand threads along the schist floor far below. The recentness of the infalls and the absence of weather erosion that so quickly tames features on the surface combined to produce an insane jumble of precariously balanced slabs and boulders, the crazy canting of which seemed to refute gravity and create a carnival fun house effect in which water appears to run up hill, and what looks level is dangerously slanted. Balance had to be maintained by feel, not by eye, and they had to move by compass because their sense of direction bad been mutilated by their twisting path through the vertigo madness of the Chaos. The problems of pathfinding were quite the opposite of those posed by wandering over a featureless moonscape. It was the confusing abundance of salient features that overloaded and cloyed the memory. And the vast black void overhead pressed down on their subconsciouses, oppressed by that scarred, unseen dome pregnant with infall, one-ten-thousandth part of which could crush them like ants.

Some two hours and five hundred meters later they had crossed enough of the Chaos to be able to see the far end of the cave where the roof sloped down to join the tangle of jagged young fall stone. During the past half-hour, a sound had grown around them, emerging so slowly out of the background ambience of gurgle and hiss far below that they didn’t notice it until they stopped to rest and chart their progress. The thousand strands of the stream below were weaving tighter and tighter together, and the noise that filled the cavern was compounded of a full range of notes from thin cymbal hiss to basso tympany. It was a waterfall, a big waterfall somewhere behind that meeting of roof and rubble that seemed to block off the cave.

For more than an hour, they picked back and forth along the rubble wall, squeezing into crevices and triangular tents formed of slabs weighing tons, but they could find no way through the tangle. There were no boulders at this newer end of the Chaos, only raw young slab, many of which were the size of village frontons, some standing on end, some flat, some tilted at unlikely angles, some jetting out over voids for three-fourths of their length, held up by the cantilevering weight of another slab. And all the while, the rich roar of the waterfall beyond this infall lured them to find a way through.

“Let’s rest and collect ourselves!” Le Cagot shouted over the noise, as he sat on a small fragment of slab, tugged off his pack, and pawed around inside for a meal of hardtack, cheese, and xoritzo. “Aren’t you hungry?”

Hel shook his head. He was scratching away at his notebook, making bold estimates of direction and even vaguer guesses of slope, as the clinometer of his Brunton compass had been useless in the wilderness of the Chaos.

“Could that be the outfall behind the wall?” Le Cagot asked.

“I don’t think so. We’re not much more than halfway to the Torrent of Holçarté, and we must still be a couple of hundred meters too high.”

“And we can’t even get down to the water to dump the dye in. What a nuisance this wall is! What’s worse, we just ran out of cheese. Where are you going?”

Hel had dropped off his pack and was beginning a free climb of the wall. “I’m going to take a look at the tip of the heap.”

“Try a little to your left!”

“Why? Do you see something there?”

“No. But I’m sitting right in the line of your fall, and I’m too comfortable to move.”

They had not given much thought to trying the top of the slab heap because, even if there was a way to squeeze through, it would bring them out directly above the waterfall, and it would probably be impossible to pass through that roaring cascade. But the base and flanks of the clog had produced no way through, so the tip was all that was left.

Half an hour later, Le Cagot heard a sound above him. He tilted back his head to direct the beam of his lamp toward it. Hel was climbing back down in the dark. When he reached the slab, he slumped down to a sitting position, then lay back on his pack, one arm over his face. He was worn out and panting with effort, and the lens of his helmet lamp was cracked from a fall.

“You’re sure you won’t have anything to eat?” Le Cagot asked.

His eyes closed, his chest heaving with great gulps of air, sweat running down his face and chest despite the damp cold of the cave, Hel responded to his companion’s grim sense of humor by making the Basque version of the universal hand language of animosity: he tucked his thumb into his fist and offered it to Le Cagot. Then he let the fist fall and lay there panting. His attempts to swallow were painful, the dryness in his throat was sharp-edged. Le Cagot passed his xahako over, and Hel drank greedily, beginning with the tip touching his teeth, because he had no light, then pulling it farther away and directing the thin jet of wine to the back of his throat by feel. He kept pressure on the sac, swallowing each time the back of his throat filled, drinking for so long that Le Cagot began to worry about his wine.

“Well?” Le Cagot asked grudgingly. “Did you find a way through?”

Hel grinned and nodded.

“Where did you come out?”

“Dead center above the waterfall.”

“Shit!”

“No, I think there’s a way around to the right, down through the spray.”

“Did you try it?”

Hel shrugged and pointed to the broken helmet lens. “But I couldn’t make it alone. I’ll need you to protect me from above. There’s a good belaying stance.”

“You shouldn’t have risked trying. Niko. One of these days you’ll kill yourself, then you’ll be sorry.”

When he had wriggled through the mad network of cracks that brought him out beside Hel on a narrow ledge directly above the roaring waterfall, Le Cagot was exuberant with wonder. It was a long drop, and the mist rose through the windless air, back up the column of water, boiling all about them like a steam bath with a temperature of 40°. All they could see through the mist was the head of the falls below and a few meters of slimy rock to the sides of they ledge. Hel led the way to the right, where the ledge narrowed to a few centimeters, but continued around the shoulder of the cave opening. It was a worn, rounded ledge, obviously a former lip of the waterfall. The cacophonous crash of the falls made sign language their only means of communication as Hel indicated to Le Cagot the “good” belaying stance he had found, an outcrop of rock into which Le Cagot had to squeeze himself with difficulty and pay out the defending line around Hel’s waist as he worked his way down the edge of the falls. The natural line of descent would bring him through the mist, through the column of water, and—it was to be hoped—behind it. Le Cagot grumbled about this “good” stance as he fixed his body into the wedge and drove a covering piton into the limestone above him, complaining that a piton in limestone is largely a psychological decoration.

Hel began his descent, stopping each time he found the coincidence of a foothold for himself and a crack in the rock to drive in a piton and thread his line through the carabiner. Fortunately, the rock was still well-toothed and offered finger— and toeholds; the change in the falls course had been fairly recent, and it had not had time to wear all the ledge smooth. The greatest problem was with the line overhead. By the time he had descended twenty meters and had laced the line through eight carabiners, it took dangerous effort to tug slack against the heavy friction of the soaked rope through so many snap links; the effort of pulling on the line lifted his body partially out of his footholds. And this weakening of his stance occurred, of course, just when Le Cagot was paying out line from above and was, therefore, least able to hold him, should he slip.

He inched down through the sheath of mist until the oily black-and-silver sheet of the waterfall was only a foot from his helmet lamp, and there he paused and collected himself for the diciest moment of the descent.

First he would have to establish a cluster of pitons, so that he could work independently of Le Cagot, who might blindly resist on the line and arrest Hel while he was under the falls, blinded by the shaft of water, feeling for holds he could not see. And he would be taking the weight of the falling water on his back and shoulders. He had to give himself enough line to move all the way through the cascade, because he would not be able to breathe until he was behind it. On the other hand, the more line he gave himself, the greater his drop would be if the water knocked him off. He decided to give himself about three meters of slack. He would have liked more to avoid the possibility of coming to the end of his slack while still under the column of water, but his judgment told him that three meters was the maximum length that would swing him back out of the line of the falls, should he fall and knock himself out for long enough to drown, if he was hanging in the falls.

Hel edged to the face of the metallic, glittering sheet of water until it was only inches away from his face, and soon he began to have the vertigo sensation that the water was standing still, and his body rising through the roar and the mist. He reached into the face of the falls, which split in a heavy, throbbing bracelet around his wrist, and felt around for the deepest handhold he could find. His fingers wriggled their way into a sharp little crack, unseen behind the water. The hold was lower than he would have wished, because he knew the weight of the water on his back would force him down, and the best handhold would have been high, so the weight would have jammed his fingers in even tighter. But it was the only crack he could find, and his shoulder was beginning to tire from the pounding of the water on his outstretched arm. He took several deep breaths, fully exhaling each one because he knew that it is more the buildup of carbon dioxide in the lungs than the lack of oxygen that forces a man to gasp for air. The last breath he took deeply, stretching his diaphragm to its full. Then he let a third of it out, and he swung into the falls.

It was almost comic, and surely anticlimactic.

The sheet of falling water was less than twenty centimeters thick, and the same movement that swung him into it sent him through and behind the cascade, where he found himself on a good ledge below which was a book corner piled with rubble so easy that a healthy child could make the climb down.

It was so obvious a go that, there was no point in testing it, so Hel broke back through the sheet of water and scrambled up to Le Cagot’s perch where, shouting over the din of the falls into Beñat’s ear, their helmets clicking together occasionally, he explained the happy situation. They decided to leave the line in place to facilitate the return, and down they went one after the other, until they were at the base of the rubble-packed book corner.

It was a peculiar phenomenon that, once they were behind the silver-black sheet of the falls, they could speak in almost normal volume, as the curtain of water seemed to block out sound, and it was quieter behind the falls than without. As they descended, the fails slowly broke up as a great quantity of its water spun off in the mist, and the weight of the cascade at the bottom was considerably less than it was above. Its mass was diffused, and passing through it was more like going through a torrential rainfall than a waterfall. They advanced cautiously through the blinding, frigid steam, over a slick rock floor scrubbed clean of rubble. As they pressed on, the mists thinned until they found themselves in the clear dark air, the noise of the falls receding behind them. They paused and looked around. It was beautiful, a diamond cave of more human dimensions than the awful Le Cagot’s Chaos; a tourist cave, far beyond the access capacities of any tourist.

Although it was wasteful, their curiosity impelled them to scratch off another magnesium flare.

Breathtakingly beautiful. Behind them, billowing clouds of mist churning lazily in the suction of the falling water. All around and above them, wet and dripping, the walls were encrusted with aragonite crystals that glittered as Le Cagot moved the flare back and forth. Along the north wall, a frozen waterfall of flowstone oozed down the side and puddled like ossified taffy. To the east, receding and overlapping curtains of calcite drapery, delicate and razor-sharp, seemed to ripple in an unfelt spelean wind. Close to the walls, thickets of slender crystal stalactites pointed down toward stumpy stalagmites, and here and there the forest was dominated by a thick column formed by the union of these patient speleotherns.

They did not speak until the glare sputtered orange and went out, and the glitter of the walls was replaced by dancing dots of light in their eyes as they dilated to accommodate the relatively feeble helmet lamps. Le Cagot’s voice was uncharacteristically hushed when he said, “We shall call this Zazpiak Bat Cave.”

Hel nodded. Zazpiak bat: “Out of seven, let there be one,” the motto of those who sought to unite the seven Basque provinces into a Trans-Pyrenean republic. An impractical dream, neither likely nor desirable, but a useful focus for the activities of men who choose romantic danger over safe boredom, men who are capable of being cruel and stupid, but never small or cowardly. And it was right that the cuckoo-land dream of a Basque nation be represented by a fairyland cave that was all but inaccessible.

He squatted down and made a rough measurement back to the top of the waterfall with his clinometer, then he did a bit of mental arithmetic. “We’re down almost to the level of the Torrent of Holçarté. The outfall can’t be far ahead.”

“Yes,” Le Cagot said, “but where is the river? What have you done with it?”

It was true that the river had disappeared. Broken up by the falls, it had evidently sounded through cracks and fissures and must be running below them somewhere. There were two possibilities. Either it would emerge again within the cave somewhere before them, or the cracks around the base of the waterfall constituted its final swallow before its outfall into the gorge. This latter would be unfortunate, because it would deny them any hope of final conquest by swimming through to the open air and sky. It would also make the long vigil of the Basque lads camped at the outfall pointless.

Le Cagot took the lead as they advanced through Zazpiak Bat Cavern, as he always did when the going was reasonably easy. They both knew that Nicholai was the better rock tactician; it was not necessary for Le Cagot to admit it, or for Hel to accent it. The lead simply changed automatically with the nature of a cave’s features. Hel led through shafts, down faces, around cornices; while Le Cagot led as they entered caves and dramatic features, which he therefore “discovered” and named.

As he led, Le Cagot was testing his voice in the cave, singing one of those whining, atonic Basque songs that demonstrate the race’s ability to withstand aesthetic pain. The song contained that uniquely Basque onomatopoeia that goes beyond imitations of sounds, to imitations of emotional states. In the refrain of Le Cagot’s song, work was being done sloppily (kirrimarra) by a man in confused haste (tarrapatakan).

He stopped singing when he approached the end of the diamond cave and stood before a broad, low-roofed gallery that opened out like a black, toothless grin. Indeed, it held a joke.

Le Cagot directed his lamp down the passage. The slope increased slightly, but it was no more than 15°, and there was enough overhead space for a man to stand erect. It was an avenue, a veritable boulevard! And yet more interesting, it was probably the last feature of the cave system. He stepped forward… and fell with a clatter of gear.

The floor of the passage was thickly coated with clay marl, as slick and filthy as axle grease and flat on his back, Le Cagot was slipping down the incline, not moving very fast at first, but absolutely helpless to arrest his slide. He cursed and pawed around for a hold, but everything was coated with the slimy mess, and there were no boulders or outcroppings to cling to. His struggling did no more than turn him around so that he was going down backward, half-sitting, helpless, furious, and risible. His slide began to pick up speed. From back on the edge of the marl shaft, Hel watched the helmet light grow smaller as it receded, turning slowly like the beam of a lighthouse. There was nothing he could do. The situation was basically comic, but if there was a cliff at the end of the passage…

There was no cliff at the end of the passage. Hel had never known a marl chute at this depth. At a good distance away, perhaps sixty meters, the light stopped moving. There was no sound, no call for help. Hel feared that Le Cagot had been bashed against the side of the passage and was lying there broken up.

Then came a sound up through the passage, Le Cagot’s voice roaring with fury and outrage, the words indistinct because of the covering reverberations, but carrying the tonalities of wounded dignity. One phrase in the echoing outpour was decipherable: “…by the Perforated Balls of Saint Sebastian!”

So Le Cagot was unhurt. The situation might even be funny, were it not that their only coil of rope had gone down with him, and not even that ox of Urt could throw a coil of line sixty meters uphill.

Hel blew out a deep sigh. He would have to go back through Zazpiak Bat Cavern, through the base of the waterfall, up the rubble corner, back out through the falls, and up that dicy climb through icy mists to retrieve the line they had left in place to ease their retreat. The thought of it made him weary.

But… He tugged off his pack. No point carrying it with him. He called down the marl passage, spacing his words out so they would be understood through the muffling reverberations.

“I’m… going… after… line!”

The dot of light below moved. Le Cagot was standing up. “Why… don’t… you… do… that!” came the call back. Suddenly the light disappeared, and there was the echoing sound of a splash, followed by a medley of angry roaring, scrambling, sputtering, and swearing. Then the light reappeared.

Hel’s laughter filled both the passage and the cave. Le Cagot had evidently fallen into the river which must have come back to the surface down there. What a beginner’s stunt!

Le Cagot’s voice echoed back up the marl chute: “I… may… kill… you… when… you… get… down… here!”

Hel laughed again and set off back to the lip of the falls.

Three-quarters of an hour later, he was back at the head of the marl chute, fixing the line into a healthy crack by means of a choke nut.

Hel tried at first to take a rope-controlled glissade on his feet, but that was not on. The marl was too slimy. Almost at once he found himself on his butt, slipping down feet first, a gooey prow bone of black marl building up at his crotch and oozing back over his hip. It was nasty stuff, an ignoble obstacle, formidable enough but lacking the clean dignity of a cave’s good challenges: cliffs and rotten rock, vertical shafts and dicy siphons. It was a mosquito of a problem, stupid and irritating, the overcoming of which brought no glory. Marl chutes are despised by all cavers who have mucked about in them.

When Hel glissed silently to his side, Le Cagot was sitting on a smooth slab, finishing off a hardtack biscuit and a cut of xoritzo. He ignored Hel’s approach, still sulky over his own undignified descent, and dripping wet from his dunking.

Hel looked around. No doubt of it, this was the end of the cave system. The chamber was the size of a small house, or of one of the reception rooms of his château at Etchebar. Evidently, it was sometimes filled with water—the walls were smooth, and the floor was free of rubble. The slab on which Le Cagot was taking his lunch covered two-thirds of the floor, and in the distant corner there was a neat cubic depression about five meters on each edge—a regular “wine cellar” of a sump constituting the lowest point of the entire cave system. Hel went to the edge of the Wine Cellar and directed his beam down. The sides were smooth, but it looked to be a fairly easy corner climb, and he wondered why Le Cagot hadn’t climbed down to be the first man to the end of the cave.

“I was saving it for you,” Le Cagot explained.

“An impulse toward fair play?”

“Exactly.”

There was something very wrong here. Basque to the bone though he was, Le Cagot had been educated in France, and the concept of fair play is totally alien to the mentality of the French, a people who have produced generations of aristocrats, but not a single gentleman; a culture in which the legal substitutes for the fair; a language in which the only word for fair play is the borrowed English.

Still, there was no point in standing there and letting the floor of that final Wine Cellar go virgin. Hel looked down, scanning for the best holds.

…Wait a minute! That splash. Le Cagot had fallen into water. Where was it?

Hel carefully lowered his boot into the Wine Cellar. A few centimeters down, it broke the surface of a pool so clear it appeared to be air. The features of the rock below were so sharp that no one would suspect they were under water.

“You bastard,” Hel whispered. Then he laughed. “And you climbed right down into it, didn’t you?”

The instant he pulled up his boot, the ripples disappeared from the surface, sucked flat by a strong siphon action below. Hel knelt at the side of the sump and examined it with fascination. The surface was not still at all; it was drawn tight and smooth by the powerful current below. Indeed, it bowed slightly, and when he put in his finger, there was a strong tug and a wake of eddy patterns behind it. He could make out a triangular opening down at the bottom of the sump which must be the outflow of the river. He had met trick pools like these before in caves, pools into which the water entered without bubbles to mark its current, the water so purified of those minerals and microorganisms that give it its tint of color.

Hel examined the walls of their small chamber for signs of water line. Obviously, the outflow through that triangular pipe down there had to be fairly constant, while the volume of the underground river varied with rainfall and seep water. This whole chamber, and that marl chute behind them acted as a kind of cistern that accepted the difference between inflow and outflow. That would account for marl appearing this far underground. There were doubtless times when this chamber in which they sat was full of water which backed up through the long chute. Indeed, upon rare occasions of heavy rain, the waterfall back there probably dropped into a shallow lake that filled the floor of Zazpiak Cavern. That would explain the stubbiness of the stalagmites in that diamond cave. If they had arrived at some other time, say a week after heavy rains had seeped down, they might have found their journey ending in Zazpiak Cavern. They had planned all along to consider a scuba exploration to the outfall in some future run, should the timing on the dye test prove practicable. But if they had been stopped by a shallow lake in the cavern above, it would have been unlikely that Hel would ever find that marl chute under water, swim all the way down it, locate this Wine Cellar sump, pass out through the triangular opening, and make it through that powerful current to the outfall. They were lucky to have made their descent after a long dry spell.

“Well?” Le Cagot said, looking at his watch. “Shall we drop the dye in?”

“What time is it?”

“A little before eleven.”

“Let’s wait for straight up. It’ll make calculation easier.” Hel looked down through the invisible pane of water. It was difficult to believe that there at the bottom, among those clear features of the floor, a current of great force was rushing, sucking. “I wish I knew two things,” he said.

“Only two?”

“I wish I knew how fast that water was moving. And I wish I knew if that triangular pipe was clear.”

“Let’s say we get a good timing—say ten minutes—are you going to try swimming it next time we come down?”

“Of course. Even with fifteen minutes.”

Le Cagot shook his head. “That’s a lot of line, Niko. Fifteen minutes through a pipe like that is a lot of line for me to haul you back against the current if you run into trouble. No, I don’t think so. Ten minutes is maximum. If it’s longer than that, we should let it go. It’s not so bad to leave a few of Nature’s mysteries virgin.”

Le Cagot was right, of course.

“You have any bread in your pack?” Hel asked.

“What are you going to do?”

“Cast it upon the waters.”

Le Cagot tossed over a cut of his flute baguette; Hel set it gently on the surface of the sump water and watched its motion. It sank slowly, seeming to fall in slow motion through clear air, as it pulsed and vibrated with unseen eddies. It was an unreal and eerie sight, and the two men watched it fascinated. Then suddenly, like magic, it was gone. It had touched the current down there and had been snatched into the pipe faster than the eye could follow.

Le Cagot whistled under his breath. “I don’t know, Niko. That looks like a bad thing.”

But already Hel was making preliminary decisions. He would have to enter the pipe feet first with no fins because it would be suicidal to rush head first through that triangular pipe, in case be met a choking boulder inside there. That could be a nasty knock. Then too, he would want to be head first coming out if it was not a go, so he could help Le Cagot’s weight on the safety line by pushing with his feet.

“I don’t like it, Niko. That little hole there could kill your ass and, what is worse, reduce the number of my admirers by one. And remember, dying is a serious business. If a man dies with a sin on his soul, he goes to Spain.”

“We have a couple of weeks to think it over. After we get out, we’ll talk about it and see if it’s worth dragging scuba gear down here. For all we know, the dye test will tell us the pipe’s too long for a try. What time is it?”

“Coming up to the hour.”

“Let’s drop off the dye then.”

The fluorescein dye they had carried down was in two-kilo bags. Hel tugged them out of their packs, and Le Cagot cut off the corners and lined them along the edge of the Wine Cellar sump. When the second hand swept to twelve, they pushed them all in. Bright green smoke seeped from the cuts as the bags dropped through the crystal water. Two of them disappeared instantly through the triangular pipe, but the other two lay on the bottom, their smoking streams of color rushing horizontally toward the pipe until the nearly empty bags were snatched away by the current. Three seconds later, the water was clear and still again.

“Niko? I have decided to christen this little pool Le Cagot’s Soul.”

“Oh?”

“Yes. Because it is clear and pure and lucid.”

“And treacherous and dangerous?”

“You know, Niko, I begin to suspect that you are a man of prose. It is a blemish in you.”

“No one’s perfect.”

“Speak for yourself.”